The Pallant House Gallery is showing the touring exhibition Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired by Her Artworks, until 16th September (previously at the Tate St Ives, and continuing to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 2nd October – 9th December). The display of over 80 female artists, from 1854 to the present day, nominally explores the inspiration of Woolf’s writings through artists who work across a variety of media, from film to photography, from painting to collage, from installation to sculpture. The mix presents a record of ‘the vast scope of the female experience’ and a scoping of ‘alternative ways for women to be’ (from the press release). Let’s own a bit of my own limited female experience here, by acknowledging from the outset that I know nothing about Virginia Woolf and have never read her work. I will be blogging again about her later this year, in a spirit of reckoning with those texts as they might relate to her family’s positioning on the Bible, especially in the light of her sister Vanessa Bell’s involvement with the Berwick Church murals in Sussex (and her photography for the same). That presents a more specific opportunity to relate the artistic-literary impulses of the Bloomsbury set to Christianity and the Bible, which does not run in the currents of this exhibition. Instead here, I found myself sifting lines of feminist art practice not from Woolf outwards, but across modernism and across photography and across the exhibition’s four themes of landscape, still life/the home, the self in public, and the self in private.

I confess myself disappointed in the shrinking of ‘the vast scope of the female experience’ to these themes. Where are the rooms themed ‘God’, ‘war’, or ‘technology’? When the exhibition does introduce a perspective of engagement that steps outside the framed exhibits, as with France-lise McGurn’s multi-coloured meandering lines painted across the walls of Room 10 (above), or with Eleanor Smith’s Shrimp Shell wallpaper-like embellishments for Room 13, these remain confined by a decorative, essentially harmless, tone for what is the more serious business of a serious story. And that in turn is failed by dislocated glimpses into whole lives of intentionality reduced to labelled observations of female bodies, vases, or fields. It is perhaps unfair to expect deeper, more rigorous, explorations of the female mind in such an eclectic and ranging collection of works, but the effect for me was to suggest that female experience aligns with precisely these qualities of eclecticism and reductive scatter-brained attention.

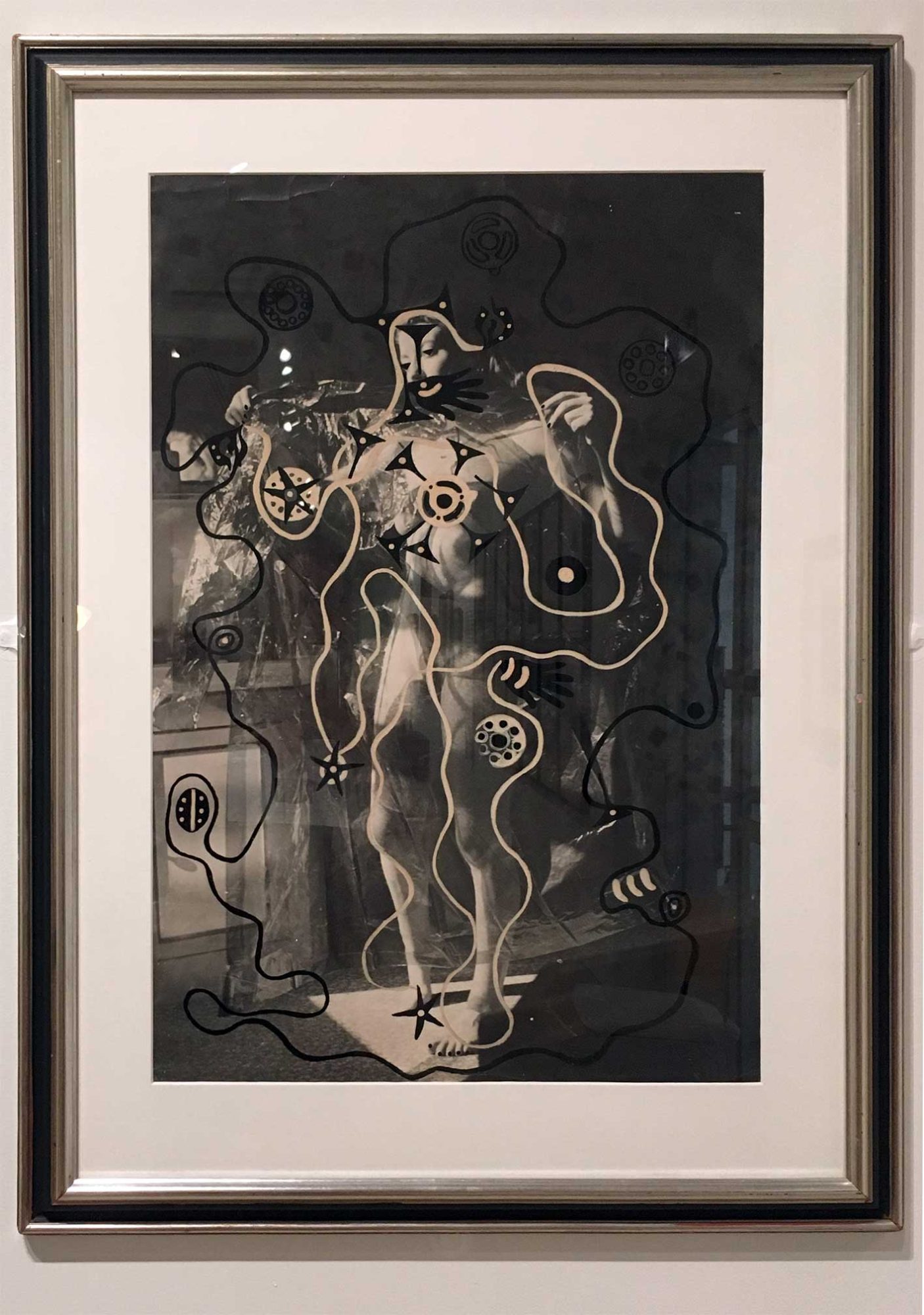

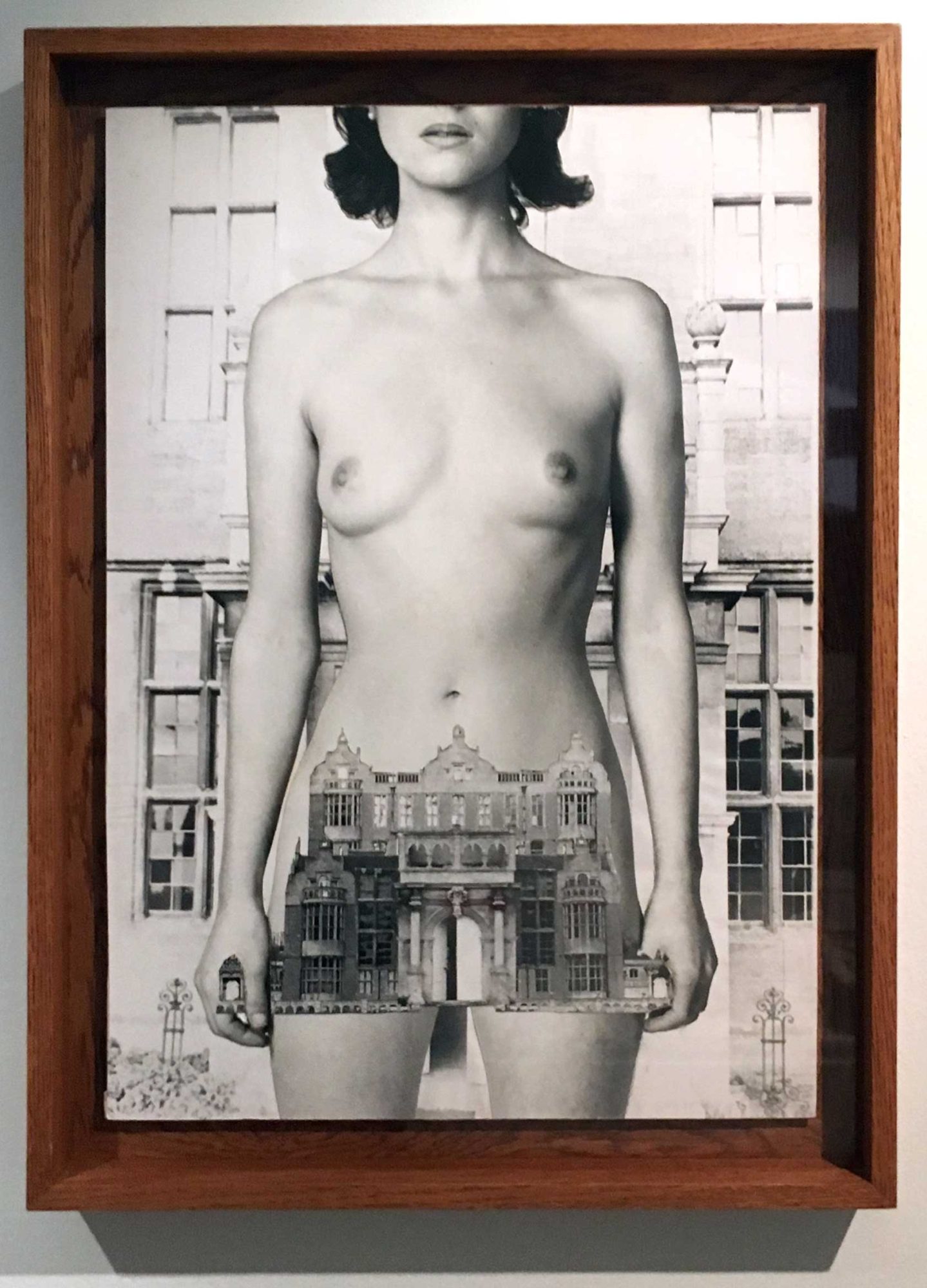

I did think, however, that photography was well-represented. In that sense, an ownership of medium presented itself through particular female artists where I hadn’t seen it before – to me, the ownership of the camera/photograph, as opposed to the ownership of painting still-life, or the ownership of minimalist sculpture practices, or the ownership of the pen, is already a very different feminist exercise. The 1920s and 1930s saw Claude Cahun pre-date Cindy Sherman with self-portraiture as a constructed get-up of identity, while Eileen Agar and Edith Rimmington take the collaged image into surrealism and the unconscious. They hustle themselves through younger conventions of the medium’s transparency, a transparency hitched to self-representation and the document and less to the objecthood of the subject. I like Agar’s dancing ‘feminine type of imagination’ (her words), and Cahun’s Judith or Salomé (not in the exhibition) become a biblical look-in before Sherman’s series of the same. A later cluster of 1970s work introduced me to Penny Slinger, Hannah Wilke, and Birgit Jürgenssen. Slinger’s series of collages over seven years, titled ‘An Exorcism’, evoke a force of emancipation that can only be expressed through pseudo-spiritual terms of release from ‘spirits of the past and other people’s ideas of them’.

Is it a mark of the museum/gallery curator practices (or funding directives) that the threads of emphasised significance, the statements about this or that art work, have to express historic value over and above other values? I felt a tension in the exhibition between historic female artists held up as exemplary for their positions in a story of emancipation, and between the contemporary female artists held up as exemplary by association with that story. The former are somehow confirmed, the latter remain unconfirmed by history, yet are pressed into that line. The former includes the small self-portrait by Louise Jopling (1877, in the gold frame, top image), a founder of a painting school for women in the nineteenth century, while the latter includes Zanele Muholi’s photographic self-portrait Bona, Charlottesville (2015, top image, right). It’s not that I think contemporary work can’t be important for history – of course it can and will be. Rather, to stress the activist, political thread here in these stridently progressive terms (Muholi brings her South African identity to questions of gender, racism, and homicide) is actually a limiting operation for what I think is the present-tense meaning of art made now, particularly photography. Recent photography categorically resists historical significance: it is life in front of us. And there is an ‘us’, into which its mode of meaning plays – not the ‘them’ of history. To speak to, or with, an ‘us’ is ideologically miles apart from the posture of ‘them’. For every expanding photographic gaze on different corners and perspectives of our world, the inscribing frame is one of collective and continuity (even if speaking of difference within it, as with Muholi). The viewing implications are of responsibility rather than influence, of a horizontal relation of humanity rather than a vertical one of intellectual patterning. As I said of another collective exhibition ‘Tribe’ earlier this year, 21st-century feminism is, I think, ‘less about feminist politicisation, more about feminine vocalisation’. We need to recognise this interactivity in the viewing and making of art in this space, and photography puts us there, centre frame.

Header image: Room 10 at the Pallant House Gallery’s ‘Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired by Her Artworks’. Photograph by Sheona Beaumont.