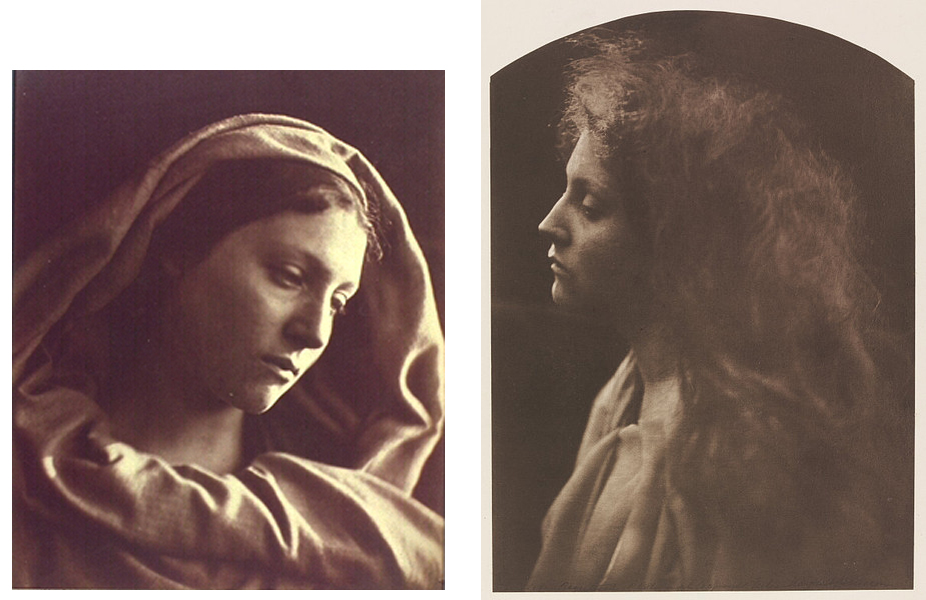

This month has been a month of recalibration, the long 8 weeks of this summer term (second half) feeling like a marathon. I’d sprinted to St Cyriac’s Day last month, a deadline for my latest project; and now somehow July has passed with my wondering where the solid ground is. Practitioner reflection brought about by 8 job/grant applications for next autumn, by my trilogy reading of Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art, Turning Pro, and The Artist’s Journey, and by my tuning in to Mark McGuinness’s podcast The 21st Century Creative. I’ve been reading/listening to quite a bit about motivation and productivity as a freelance, and there has been so much useful, insightful, fog-lifting, challenging counsel in the above. I could make a list of those gems, all very mindful and productive. But none of them came near to the particular circumstances of a working mum. In fact, I kept getting very annoyed. Annoyed at how disenfranchised I continue to feel at the creative party that is the modern day portfolio or freelance career. Annoyed at the lack of female voice, and the mother in particular. Annoyed at aspirational optimism without the reality checks of family needs.

So I asked myself to write this post, at least in part to try and articulate what I actually am up against, what is actually at stake with art and motherhood. And I came up with the idea of front lines. Actual front lines, not obstacles or challenges to be swept aside and overcome with neat assertion. By which I mean I have to negotiate the presenting differences in what I want to do, and what I can do, daily, over and over again. I HAVE to enter the fray with malleability and responsiveness and commitment, otherwise my sanity will be shredded. The issues are of identity, not just of management of a circumstance/situation, which to the external (usually male) eye view may simply be practically accommodated. They plumb deep cultural associations, and they mine sense of self.

So here we go:

- Emotional labour. Emotional labour or load has only recently been identified in the world of family life (in parent/child relations, and in marriage) as the concerted human effort behind a family’s daily arena of coordination and communication. The carrier of the financial load in family life is unsurprisingly well-identified – whether the father or the mother, the breadwinner is a traditional keystone around which the needs of childcare, housework and sustenance are arranged. But the carrier of the emotional load has arguably as central a place in the family home, a place where the demands of parenting are concentrated around one or more small dictators who change the rules/furniture every hour. There is no simple dualism here, but if you are the person at home who carries most of the emotional load AND you are trying to work part-time as a creative, then the pressures you face are particularly emotionally intense and exhausting. I remain surprised at how little emotion features in any of Pressfield’s descriptions of ‘turning pro’ in the world of creative work. He holds up child-birth (and noticeably not child-rearing) as a parallel exceptional achievement by women – commendable for its comparison with the warrior-pro mindset, as unhesitatingly committed to ‘do the work’ (= labour). But the expression and experience of emotion is downplayed in what is a cool-headed levelling of human function and focus. Yet both child-birth and child-rearing are front lines of emotional labour through or alongside which women are encouraged to work – often without reckoning of the turbulent, shifting, alternatively myopic and magical stresses this involves. The contradictions are many, but I’m looking for compounded benefits too. It’s not enough to say that ‘turning pro’ requires the wholesale rejection of emotion, we need a richer way of talking about this kind of work.

- Multi-directional responsibility. I’ll also call this required selflessness. There’s a prevalence of the self in the working practice of a self-employed creative. The artist needs self-control, self-discipline, self-knowledge, self-doubt – and the exertion with self over self is undoubtedly a part of the road to maturity for all of us. For Pressfield it’s about getting to the real you. But in family practice, and in parenting practice most certainly, the dependence of children encroaches on this kind of self-introspection. ‘Normal’ adult social boundaries, conventions of communication, personal space, and relational signals are thoroughly challenged (WARNING – emotional labour reaches gigantic proportions here!), let alone ones that put a high value on solitude. The challenges of daily interaction with people who can’t yet dress themselves demand a grown-up response, a response which has to concern itself with the development of a new little person, not just the adult. It can be a long hard journey to self-responsibility, but it hits the ball out the park to learn multi-directional responsibility on the journey with children. It is nothing less than a full-frontal, direct assault on the ego, where the daily instinct of self-assertion (prized in creative practice) has to learn a different dance of side-steps, reaction, distraction, consolation, coercion – sometimes just to keep a room quiet and a child fed and/or clean. It naively misses the point to merely separate a world of adult work from a world of child development – though there are plenty of guidelines about how to do that, how to better ring-fence your ‘own’ time. This frontline is epic. It is where love does most of its real human shaping, in something relationally reflexive and multi-directional. That kind of unseating of the self needs a greater say in the focussing and articulation of creative practice.

- Seasonal growth. I don’t find that my life and circumstances respect the idea of linear career progression or learning. In early parenthood, I well remember that most reassuring consolation from other parents, ‘It’s just a phase’ – at the confusion of growth spurts, the dropping of daytime naps, periods of teething etc. Now with young children, my months are defined by the school year, with weeks of activity across termly/holiday boundaries. These are also shaped through patterns of church liturgy and the church calendar, which in turn reflects seasonal changes such as the amount of light in my day, or whether it’s springtime or harvest. Not least, as a woman I experience a monthly cycle, a living embodied practice of variegation in mood, focus, and energy. These are real enough, and pressing enough, to insist on adjusted and constantly adjusting expectations of productivity. Models of career progression, even if shaped through understandings of portfolio careers, tend to assume a kind of consequential linearity. A logic of linearity informs descriptions of employment, we can draw lines from one position or project to another, and indeed trace life’s passing along time’s numerical calendar. We can apply ourselves to advancement along this calendar. Well of course that’s an obvious thing to do, and all very useful up to a point – but it’s also like a straight rod of iron applied to the measure of the human form. We work in curves. Life has circular rhythms. Our energy ebbs and flows. There’s a whole wisdom tradition about living in such as way as to cultivate these patterns, and to work with them. It’s a different paradigm from the conventional modern world of work, a world where the creative journey is otherwise grossly misrepresented by a linear work ethic – more often beholden to capitalist ideals and the production line. Seasonal growth is so devalued by first world culture that we experience guilt about periods of ‘fallow’ or slow or repetitive time – yet these are good and rich, even when they don’t pay with pound signs.

I wonder about this stuff a lot. I feel like some vocabulary, some sense of intuition, related to being female, is only barely being articulated here by me. Maybe there is more to come.

Header image: School Sports Day, 2019, by Sheona Beaumont.