I’ve seen quite a few Hirst pieces in my young art journey: at the landmark Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1997, and up to recent appearances in Gloucester Cathedral and Bath Abbey – see Artsy about him. I’m always conscious that it’s impossible to ignore him on the British art scene, but the levels on which I have been interested in his work have nevertheless remained at something of intellectual distance. I’m not shocked by his work, and I don’t dislike it, but there is a sense that I take them on as a kind of conceptual exercise, toys to play with in terms of imagery that gets me thinking – whether the references to disciples and saints, to visual religion, to butterflies. I’ve been recently excited by the techniques of digital foil printing and lenticular printing that he’s employed – glad that he’s doing it, and finding the results quite beautiful at times (‘For the Love of God’ as a 3D lenticular) – but the explosion of his self-marketing has a slightly hollow inflation which I haven’t quite settled in my head.

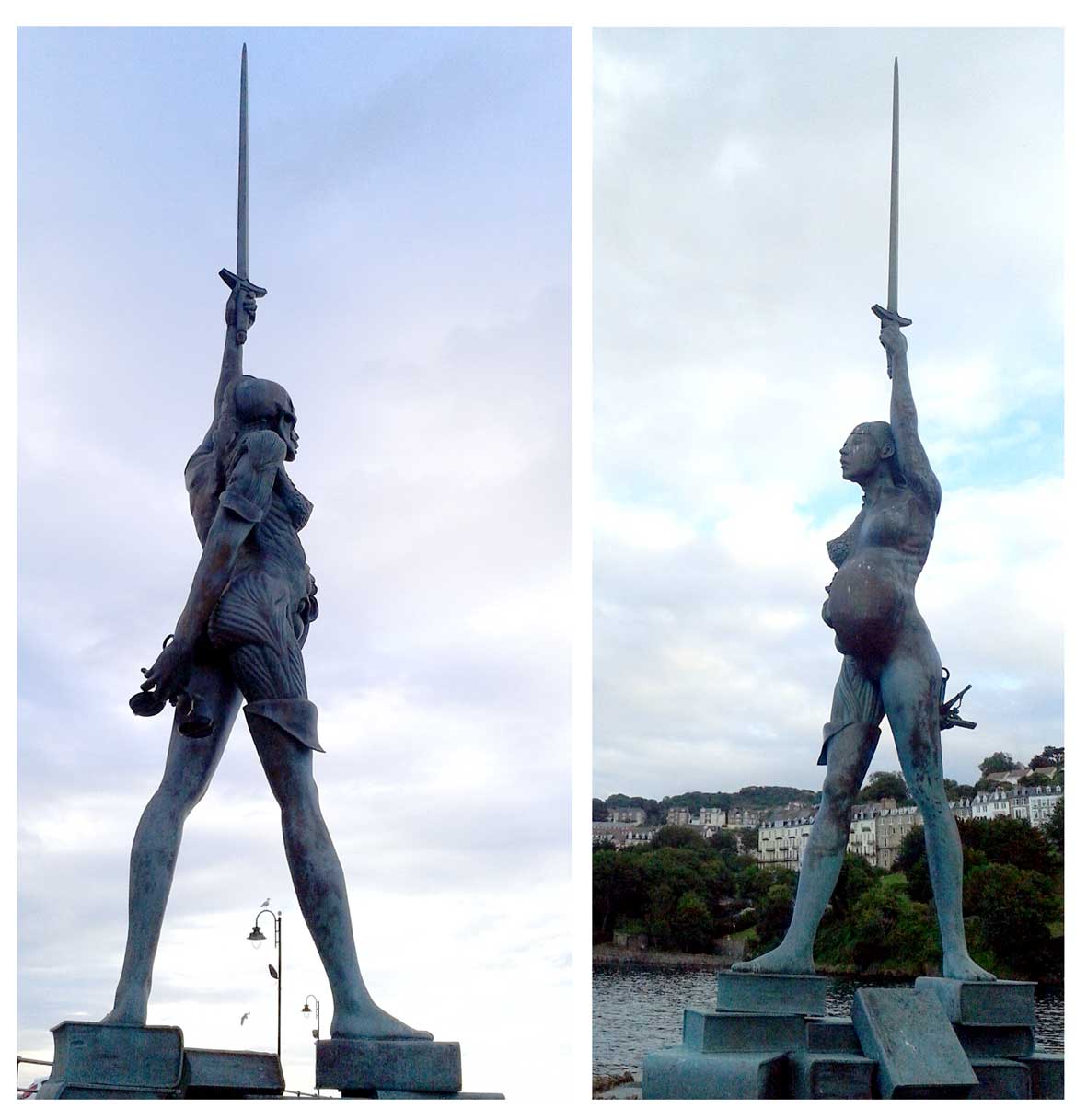

So it was something of a surprise to find that when I met Verity, on holiday in Devon last week, I was deeply moved by her. Verity is a 20-metre bronze-clad sculpture sited on the harbourside of Ilfracombe, a recent loan to the town where Hirst lives nearby. She is certainly a talking-point, and since installation last year in October, has received much negative and positive press about the connections and benefits she brings to the area – largely negative on the aesthetic response. She stands facing out to sea, in a pose that deliberately recalls Edgar Degas’ Little Dancer (c.1881), one side of her showing unmarked smooth skin and countenance, the other revealing a stripped level of skull, muscle and foetus. She holds a sword aloft in one hand, and scales in the other, while standing on a pile of law books – she represents Justice and truth.

For me, her monumentality had everything to do with being pregnant and exposed. She seems to exude both triumph and indifference in her state, without being locked into any male gaze of suitable womanhood, desirability, appropriateness etc. She doesn’t have a certain confined self-consciousness – or rather it’s more like a self-possession that means she can stand with her back to the town and the glances of others without seeming to hide. The exposed baby is key – the pregnancy is internally felt by her more than it is externally assumed by others. I love that. I felt an affinity with not just her, but Hirst who has in some way recognized a particularly visceral, interior burden and not simply a rounded glorified symbol of fertility (and/or nudity). This woman’s corporeality is the same as that of Virgin Mother – Hirst’s 2005 version of this sculpture without the objects in hand or under foot. She is not demure, she is feminine, she is humanity doubled – as receptacle of new life she is not just a passive recipient of something external, but rather the configuration and conjunction of internally-borne life, wrestled life, bloody life.

Header image: Verity, 2012, by Damien Hirst; stainless steel and bronze. Photograph by Sheona Beaumont.