The recently published report (Dec 2018) from the Arts Council, Livelihoods of Visual Artists: 2016 Data Report, found that 90% of visual artists in the UK don’t make enough money to live on. Across the 2,000 artists surveyed, the average income from art practice was £6,000. This is further skewed by a small number of higher income artists raising this representative average, where in fact two-thirds of artists earn less than £5,000 (see p.9 of the report).

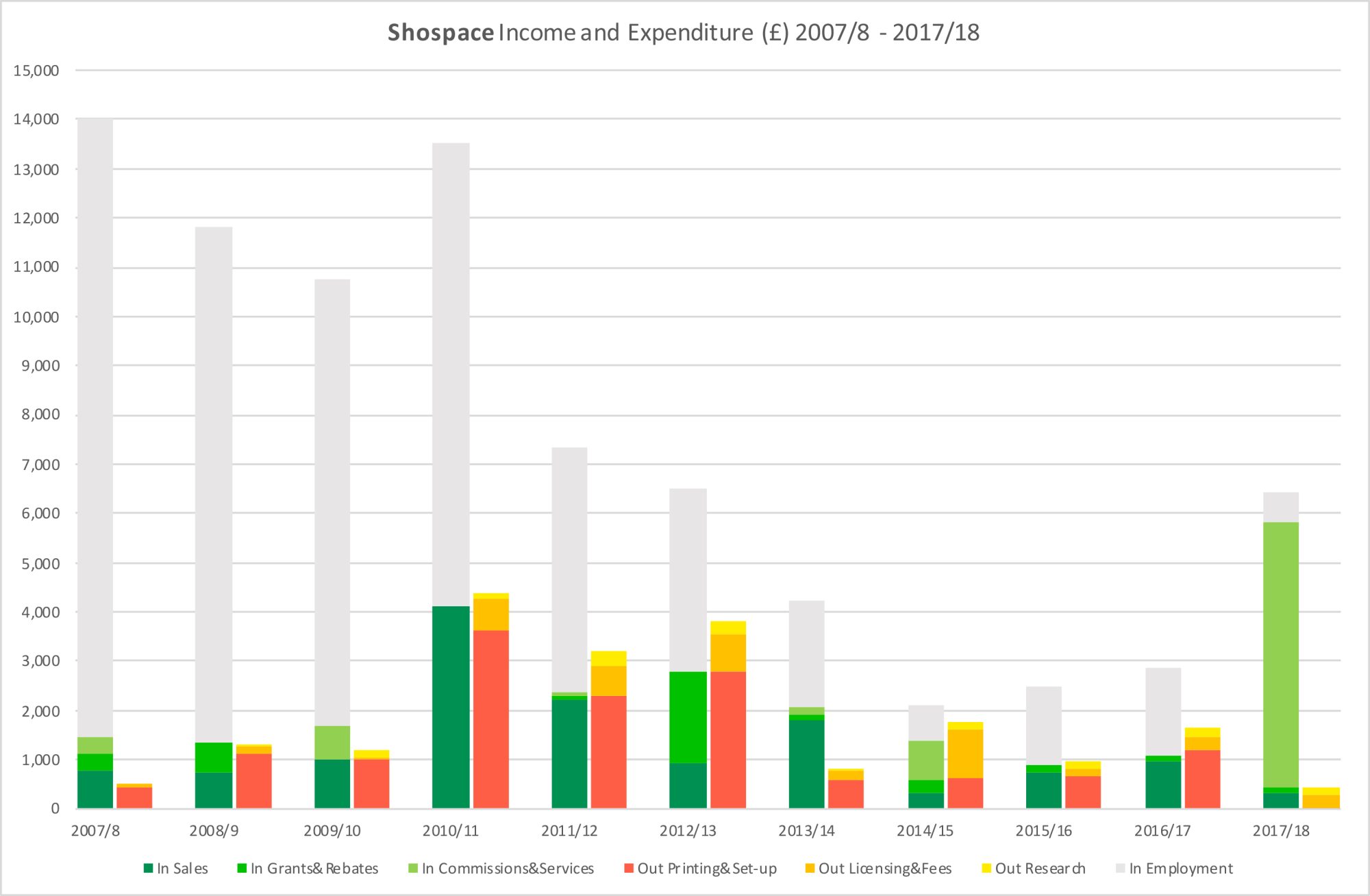

I’m taking the opportunity to review and present my own self-employment practice in the interests of transparency here. I’ve worked part-time in art practice for nearly twenty years now, at first in an ad hoc way during and after graduating, then registering as self-employed in 2007. The bar chart above summarises my Shospace business for the 10-year period since then, with income and expenditure shown side-by-side for each year. It’s probably safe to say I’m reaching mid-career stage now, but one of the consistently hard issues to deal with is that my practice income is not remotely self-sustaining (the greyed-out income shows earnings from additional employment after tax: firstly in libraries, then as a grant during PhD studies, more on supplementary income below). Of the 10 years represented in my chart above, for 6 of them I declared a loss with regard to Shospace, since direct costs for making the work exceeded the income. Even in 2011, when I sold nearly every print and numerous catalogues from a solo exhibition of 25 works (making Bristol Through the Lens my most ‘successful’ exhibition), the costs of printing and gallery hire just overtook the sales.

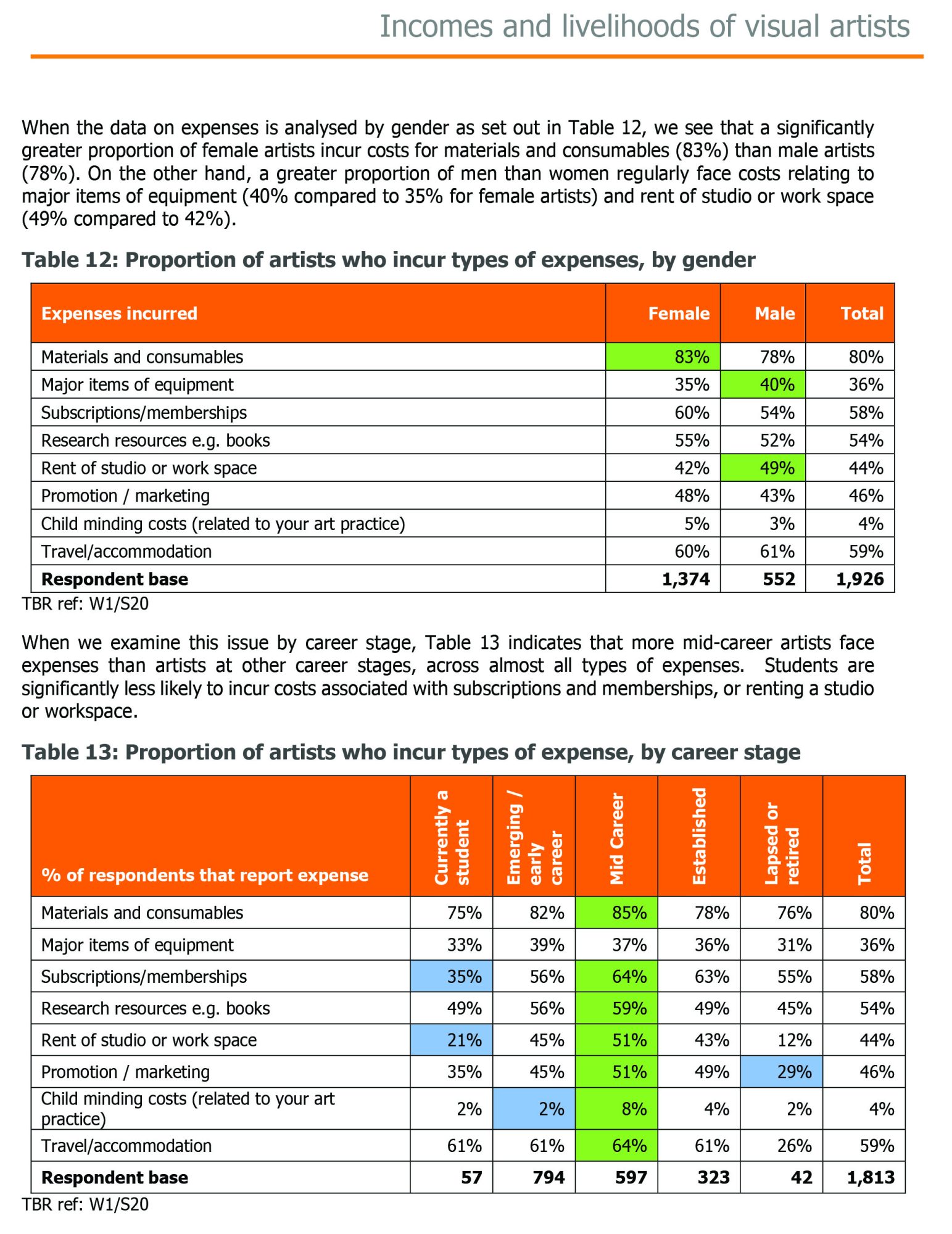

In individual art-making, this is an emphatically different situation regarding the administration of one’s job – employment in other sectors rarely costs the worker this kind of expenditure. And further, it’s often a vicious circle: you need money to make the work, and to get money you need to sell things you’ve made. Further still, according the to survey, mid-career female artists are the group facing the biggest expenses (p.31, below, with childcare unsurprisingly being a feature). In my case, despite the support of generous tax credits for childcare, and despite the low overheads caused by working from home in church-managed properties, it is the inflexibly-coupled linking of work and expense that has most specifically inhibited my business’s growth, which I’m sure is the story behind many unmade, unrealised, artist projects universally. Even where a full-time artist would probably show greater progression or expansion over 10 years, I don’t believe there is gradation or drop-off in this linking of income with expense – a friend of mine whose photographic career you would describe as ‘taking off’ says the achievements are illusory, because she’s spent more than she’s ever spent on prints, books, exhibitions etc. Unless your work reaches the world of the super-rich in the upper inflations of the art market, there is no stable business model here.

Now why am I highlighting this? I’m not getting the violins out, this isn’t a woe-is-me lament, nor a presumption of money growing on trees. I’ve been self-righteously sad and angry in turn with previous projects, and in trying to get that element out of the way, I’ve learnt that one’s perception of ‘earning’ has to reckon with a personal burying of entitlement. It’s a familiar enough life lesson that one has to learn to deal impersonally with rejection, or unrealised potential. But the modelling of artistic practice as a livelihood (if not necessarily a career, as we note the careful choice of the report’s title) does have to reckon with this mode of production (if not necessarily profit) and its viability. The pursuit of art practice is one choice amidst a wealth of choice in our Western educationally privileged society, and it is almost inevitable that we are schooled into comparative career assessments, charting what we do against what we can get out of it, often through the aspirational language of business development and the capitalist dream – but such assessments misrepresent the kind of delimited, grass-roots existence that such de-institutionalised practice is. Supporting structures for other livelihoods involving practice, such as medical practice, or agricultural practice, tend to offset the costs or the direct carrying of costs by the practitioner: there are centralised pay structures (such as the NHS), or governmentally-ratified policies and investments (such as farm tenancies and quotas) and such large-world structures contribute to (and legitimise) less direct mediation of and accounting for ‘craft’. But artistic practice is very much up against its small-world individual binding of cost-to-production, which while it assumes the same vocational circuitry as some of these other practicing professions, is far less equipped, mediated, or measured through societal or institutional organisation. Or even talked about in these terms.

So what are the options? The most obvious is seeking supplementary income, as recognised in the report (p.81ff, 7 out of 10 artists have other jobs, nearly half of these having 2 or 3), and in my own experience. The effect is often double-sided, however, the report acknowledging that time and energy spent elsewhere necessarily diminishes time and energy for art practice – I well relate to the feeling of living two lives with my earlier jobs in administration, or in council and university libraries. Over time this is a false economy, and the splitting of self can become detrimental to mental and physical health, though I don’t doubt that for some there is little choice in the need to earn. More recently for me, a change in the nature of my business, stepping sideways into research rather than practice, and finding thereby a contract for services (rather than raising money through sales of art work) has taken my income over the £5,000 mark for the first time. Coming from the church (specifically the Bishop Otter Trust), it’s not that far from an old-fashioned model of patronage, which would have been an option in earlier times of societal/institutional organisation for artists. It certainly reflects my inclination of wanting to find work in related forms, and in my case this is a move towards the top type of secondary-income job held by artists according to the report – that of lecturer/academic (closely followed by teacher, see p.84).

The troubling extended consequence of seeking income elsewhere is the likelihood of artistic practice diminishing and even ceasing. Indeed, stopping is another option; the report’s data depressingly suggests that of those considering stopping, mid-career women married-with-kids are pretty much at the top (p.66ff). Further, by art form, photographers experience lack of financial return as the greatest barrier to developing practice (p.106), despite being at the top of the list for total income (which includes non-art-practice income. At the top of the charts for average practice income alone are craft, sculpture, ceramics, illustration, and community projects, p.13). This wouldn’t be the first time I have considered stopping, and in fact I think I did once decide to leave it behind, only to find I couldn’t not do it – I couldn’t stop dreaming up and tinkering with visual ideas.

So I think I’ve accepted the impulse, but I’m seriously questioning the model, and in particular the viability of material production. It’s one thing to say I have a body of new work on the theme of motherhood ‘on the go’, it’s quite another to pursue its realisation in print or on the wall. The reality is that I need more than £20,000 to produce it, and that I’ve sought funding since 2014 on 3 separate occasions which has been unsuccessful, despite committed institutional support for its display and promotion. There is potential to crowdfund or patron it, or even to commercialise a lenticular process that I’m exploring with it, but even then its reach wouldn’t extend to income. It’s also possibly publishable as digital content, minimising production costs significantly, but again, income and impact would be correspondingly small – a reflection of the ‘shallow’ online market, with its fast and devaluing dissemination of digital visual culture. It doesn’t seem like a winning situation. In truth, the cold reality of costs here pushes me to scope and think and pray for a return on my effort in different ways: the waiting for a ‘right’ fit with an as-yet unimagined context for the work, expecting/seeking relationship out of it instead of money, shifting the value of productivity to something seasonal and organic (rather than black or red columns), and as a Christian choosing to trust God’s model for growth through kingdom and character rather than through economy and numbers. I don’t find it easy to accept, but then it’s a good reminder that we’re all ultimately works-in-progress aren’t we?

Header image: Dicing with Creation maquette, 2012, by Sheona Beaumont.