Photographing celestial events is something I can’t resist. I’ve had my camera trained on the Venus & Jupiter conjunction of 2012, two eclipses in 2015 (one lunar and one solar), and tonight’s blue supermoon. My approach is decidedly non-technical. With wildly varying results, I find out things at the time that either help or hinder what is a remarkably difficult scene to capture. Things such as realising that I can’t see the settings buttons in the dark, or that sitting in the car can create a frame and shelter from the rain. Lens misting between sequential shots when the temperature outside is below freezing – that made for a long night.

Tonight, unexpectedly, was a story in motherhood as much as in moon-gazing. The business of my business often doesn’t fit the procedural, strategic, model of efficiency that one might imagine of photographic employment. That’s primarily because it’s a form of photographic self-employment that meanders around artistic impulses, constellations of interests (rather than programmes), and unpredictable hours. But it’s also because I am a mother. My visit to the nearby Abbey, at around 6pm, was loudly scrambled in between toast-parcelling tea to my 7- and 4-year-old children, enthusing about the sky while getting 3 bodies into 3 layers of clothing each, yelling out ‘who last saw the tripod’, stopping the kids running into the road to find the moon, checking the alignment of moonrise online, and wondering if this was a good idea. Today it felt like a cheerleading crowd of enthusiasm, on another day it might have felt like being shot down in flames. Admittedly the enthusiasm was carried by me later in the evening as the cold, the mud, and the dark didn’t seem so exciting; at one point the serious conversation about ghosts and faces in the trees took place in between exposure counting (for the ghosts to go away) and making shadows of our own (with my phone’s light so I could see where I was putting the tripod). But the kids found the stars amazing, and my daughter pointed out a silhouette that I would have missed, while we played ‘I spy’ waiting for more height.

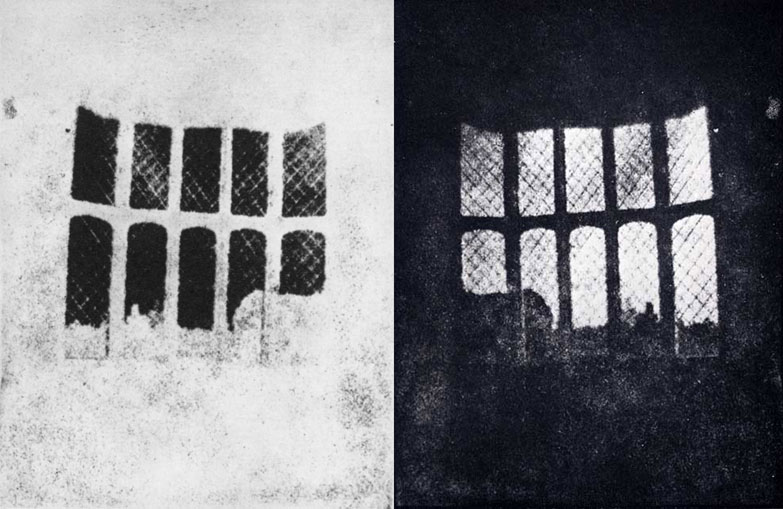

Here’s the thing: both the kids and the moon invited another way of working. The individualistic self-directed self-determining professionalism of orderly working practice is the norm. It’s like doing photography in the daylight, even like Talbot’s way of doing photography might have been. Photography at night, however, is somehow wayward, tinged with suspense and the hovering feeling that you are not in control, not even the centre of your universe. Having kids around is precipitous and galactic; seeing the moon so luminously brilliant asks that you look twice, through doubling exposures, and reflected uncertainty. My UV filter played tricks in these images, creating a rather fitting additional blood moon in an in-camera reflection. I also had over twenty dud shots. But in that slightly crazed patterning, there’s also a bigger, slower, slowed, identification: the moon carries on in stately rhythm, the superstar kids grow in their orbit around me, and the world is miraculously held together. When I spent time tinkering with the images later, that’s the feeling I was soaking up, and that’s where I want the images to come from.

Header image: Sharrington Tower in the Moonlight I, 2018. Photograph by Sheona Beaumont.