Missionary photography is outside the main interest of my research by virtue of its departure from biblical representation. However, it is undoubtedly a significant aspect of photography made and published in the name of religious interest, from its first occurrence in the mid-nineteenth century, up to the present day. There are certainly instances of biblical focus, but they remain subservient to the broader aim of mission focus, which can vary from documentation of indigenous cultures to reports/celebrations of material and spiritual progress. Such images certainly seem unconcerned with artistic or reflective nuance, though as I go on to mention, they perhaps offer a noteworthy check on the marshalling of representation in the name of ideological purpose.

T. Jack Thompson, in his book Light on Darkness? Missionary Photography of Africa in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, highlights uses of photography which range from scientific and anthropological interest during Dr. David Livingstone’s 1858-1864 Zambezi expedition (see above) to the atrocity photographs of Alice Harris showing mutilated Congolese during King Leopold’s era (1865-1909). Photographs both posed and emotive were believed to be demonstrative of ‘Africa as it was, not simply as [the photographer] saw it’ (p.273) and were more often than not accompanied by images taken to show the (successful) work of the missions themselves. In one interesting case, a photograph of a black missionary to Malawi taken around 1878, is later doctored in the 1924 publication of the Laws of Livingstonia (by W. P. Livingstone) so as to show the man holding a Bible. Originally part of a group photograph, the solo portrait of William Koyi takes on the singular authority of a ‘man of God’, albeit one dressed as a European, with the representative token of purpose and position. Similar doctoring occurred with figures who were never converted (p.156-158).*

In this sense, the Bible explicitly figures as an anchor for certain ideas about Western civilisation and the expansion of the Empire. There is no inherent textuality about it. It is an object wielded (at least pictorially) to help ‘read’ the identity of the person shown, but not itself to be read or internalized. It is Bible-as-symbol, much as it appears in countless photographs of confirmations or as the accessory of choice in early society portraits.

* Incidentally, in 1908, American athlete Forrest Custer Smithson was photographed jumping a hurdle while holding a Bible in his hand, supposedly in protest at being asked to run on a Sunday in the Olympics. However, this photo, too, turns out to have been ‘faked’ – this time by posing after the event.

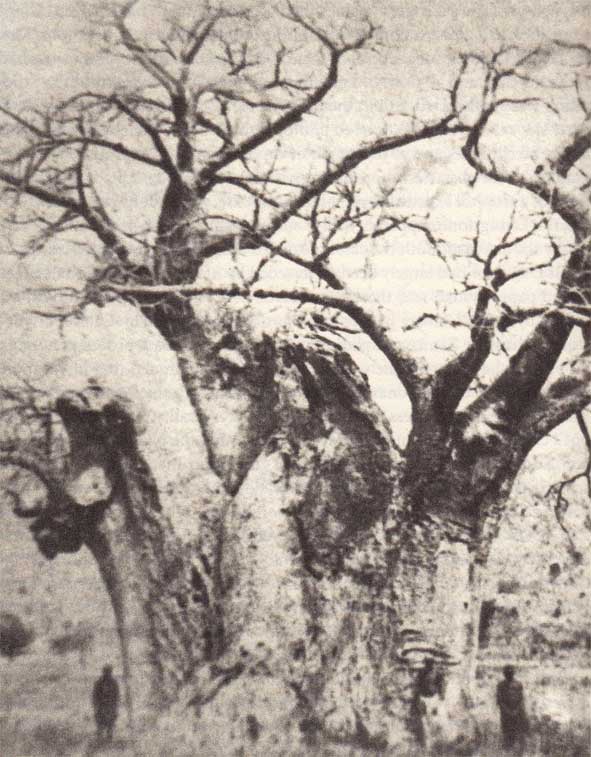

Header image: Baobab Tree, c.1858, by Charles Livingstone.