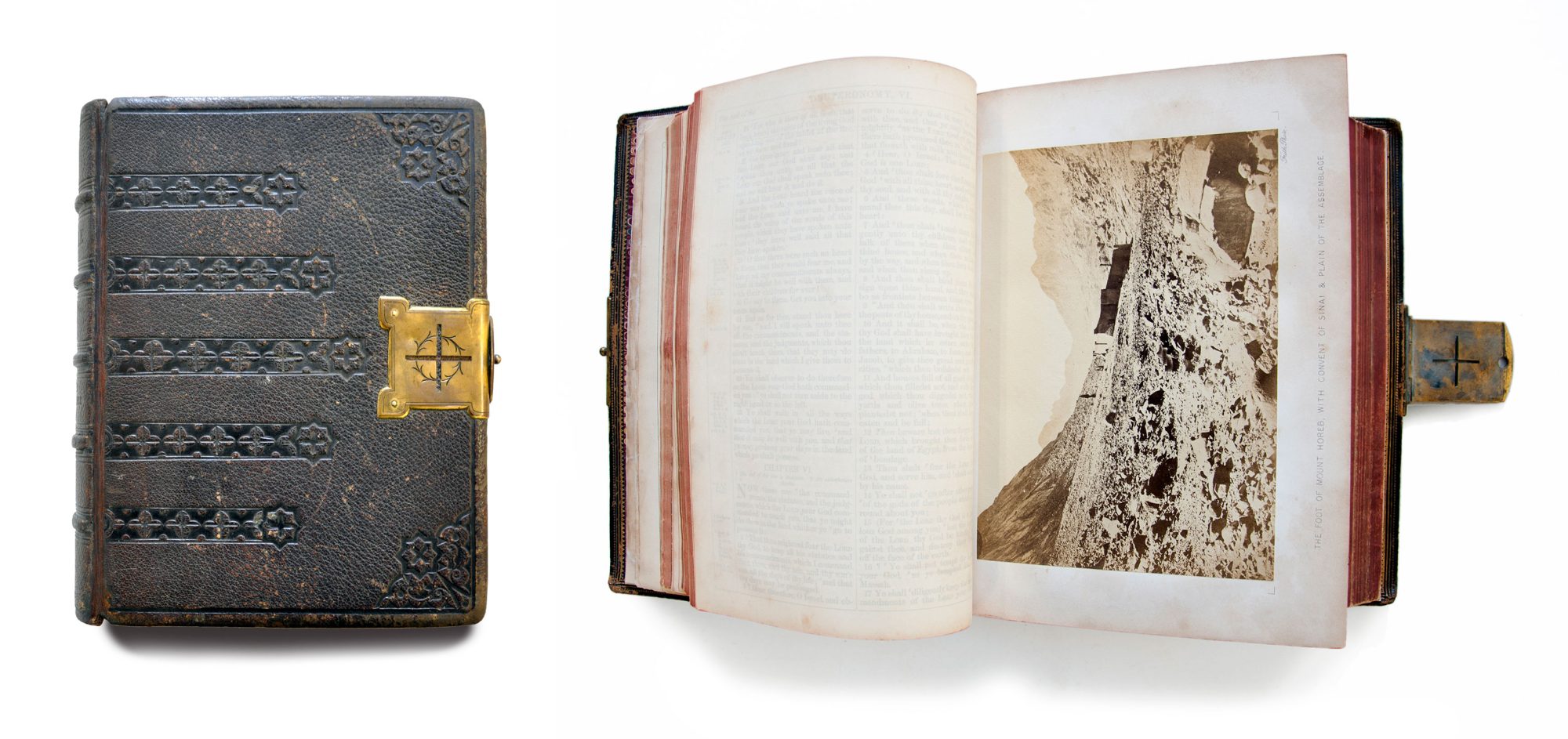

This month I’ll be speaking at the University of Oxford’s seminar series ‘The Bible in Art, Music, and Literature’, with a talk entitled ‘Pick & Mix: the non-linear Bible as modern artists visualise it’. I’ll be exploring a few artists discussed in my recent journal articles, but also introducing some thoughts on Francis Frith. Frith’s albumen prints were the first to illustrate a Bible in 1861, as seen above. In many ways, what he did with photographs of Palestine anticipated the range and breadth of new, modern ways to visualise the Bible. I’ve called this a pick & mix approach, not to be derogatory, but to argue that for him and for others something positive is going on with respect to the interpretation of the Bible in visual culture – the recasting of its language and stories as essentially non-linear. Here, I expand on what this meant in Frith’s case.

Frith travelled to Egypt and Palestine three times between 1856 and 1860; during and immediately after the trips, he published at least eight titled works, including this and a following two-volume ‘Queen’s Bible’ – the first photographically illustrated Bibles. These were undoubtedly at the more formal, exclusive end of his commercial printing enterprises, which also included serial travel books, sets of stereoviews, illuminated visual presentations, and card- and glass-mounted views sold separately. Frith delighted in the immersive effects of photography – his were not the typical wall-mounted print set for exhibition in societies. In his hands photography had different work to do, conjuring up the travel experience and imaginatively engaging the viewer to transport them to another world.

More than this, Frith was a Quaker (later a minister), and the idea of transport had a lot to do with seeing and experiencing something true – in this case, with a lens on the landscape of Egypt and Palestine, it was exposure to its meta-truth as read in the Bible. Frith’s Bibles are inserted with topographical views of particular places (such as Bethlehem, Mount Sinai, and Jerusalem) on separate pages. They interrupt the seamless verbal script, offering a conceptual junction with the real world. It isn’t simply a case of illustrating the text, it’s the alignment of another space with, alongside, through, the text. It’s a new epistemological venture. Truthfulness as it might be read has now a spatial dimension as something that might be inhabited. Frith found that the photographic image made immediate, spiritual claims on the viewer:

We can scarcely avoid moralizing in connection with this subject; since truth is a divine quality, at the very foundation of everything that is lovely in earth and heaven; and it is, we argue, quite impossible that this quality can so obviously and largely pervade a popular art, without exercising the happiest and most important influence, both upon the tastes and the morals of the people. … We protest there is, in this new spiritual quality of Art, a charm of wonderful freshness and power, which is quite independent of general or artistic effect, and which appeals instinctively to our readiest sympathies.

Francis Frith writing in ‘The Art of Photography’ in 1859 (emphasis original).

Such a charm of wonderful freshness and power becomes, in contemplating biblical sites, a matter closely related to faith. The past is realised in order to enliven a theological imagination. The reader-viewer may well connect with the romanticism of the picturesque view, may indeed connect with the factual visual information pertaining to ancient biblical sites, but the trump card was really that they might connect with the living truth of God’s activity in the world (as much present as past). The facingness of the world exerts its non-linearity on biblical reading here. And in so doing, Frith I think sees in miniature the effect of big screen photographic representation – that catapulting of realistic spectacle and immersion which has rendered the Bible extra-textual in so much of our modern visual culture.

More at the seminar… And for those that can’t, some of these ideas are being worked into an essay for an edited volume, to be published with Routledge later this year (Transforming Christian Thought in the Visual Arts: Theology, Aesthetics, and Practice).

Header image: The Holy Bible, illustrated with photographs by Francis Frith, 1861. Photograph by Sheona Beaumont.