This week, the churches closed. The coronavirus spreads worldwide, and in line with a governmental announcement curbing all social gatherings on the 23rd of March, the Church of England confirmed the closure of all church buildings on the 24th.

There are so many ripples and ricochets felt as the doors are pulled shut. Permit me, if I may, to add a reflection based on my own church, St Cyriac’s in Lacock, Wiltshire – a small offering of wonder and lament. Let me say first that I understand, and agree with, everything about church community existing in the people, rather more than the building. I recognise that to pray, worship, and serve is taking faith into new spaces, and that beauty and truth will grow differently as a result – I’ve seen it in small ways already; my family’s singing, on broadcast services, and in my husband’s parish newsletters. Amen for this.

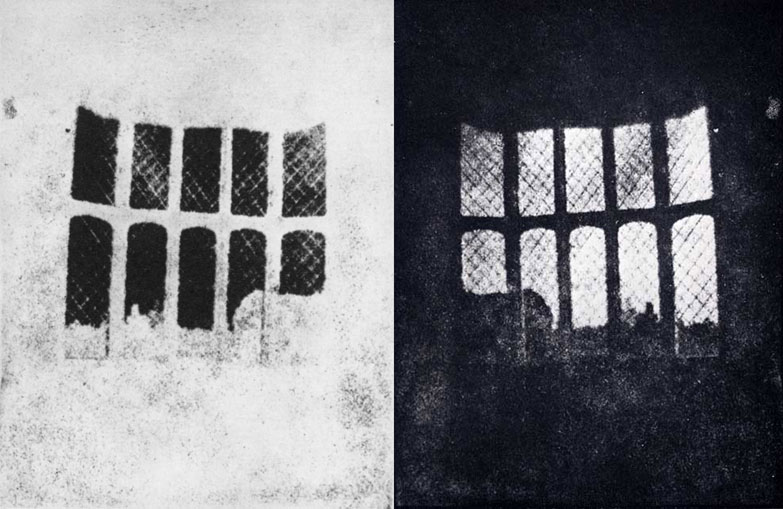

But here, just for now, I mean to see the building, to hover at the door, listening to the silence. I resonate with the Dean of Westminster’s words, reflecting on the closure of Westminster Abbey, that it feels like a hard thing to close the doors on a building that speaks. And for me, St Cyriac’s speaks volumes. This time last year, I took over a thousand photographs of the place. I immersed myself in its material culture (from the cockatrice on top of the spire to the hare curling round a pillar), in its setting of Easter time through candles and curtains and cups, in its history from knights to cameras, in its life unfurling as people came and visited, cleaned and prayed, sung and whispered. I did this primarily for a project of reinterpretation – to write a new guidebook and produce new postcards. But now they have a poignancy, typical of photographic documentation, of something not just passed, but of something silenced.

One of the things that makes a body of photographs work, that connects the images like words in a sentence, is the consistency of visual language or content – and here it’s the church. St Cyriac’s as I’ve seen it is a language, not just a symbol. With its own dialect (probably West Country). It transcribes and translates my community’s fumbling expressions of what it means to be human both physically and spiritually. Depending on your faith position, it can be like a relative who reminds you ‘what things were like in my day’, or it can be like material mindfulness in spoken word. It can be a thick accent with the clod of tradition, or a pure echo of light and air. It can only sound like this because it’s been talking for hundreds of years, a veritable wisdom tradition in its own right. I struggle to shut it out of my mental and emotional landscape, which is why it is so odd to be shut out of it.

Fundamentally here, what I want to remember is that stones and mortar have this kind of vitality, this kind of contributing conversation, for people doing their wondering (and wandering) out loud. When Jesus pointed out that the stones of Jerusalem were bursting to talk, I think he shone this light on their language. I for one don’t want to lose the accent.

Header image: Doors (St Cyriac’s Church, Lacock, 24th March 2020), by Sheona Beaumont.