(This by way of a personal response to both Frances Spalding’s John Piper, Myfanwy Piper: Lives in Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009) and the exhibition John Piper and the Church at Dorchester Abbey, 21/04/12 – 10/06/12)

- Piper was a writer before he was an artist. His pre-war work (after a failed solicitor’s training, and a half-completed artist’s training at the Royal College of Art) was mostly in critical writing, whether reviews of art or architecture (especially churches), and also in poetry: 1923 and 1924 saw him publish his own collections of poems – Wind in the Trees and The Gaudy Saint and Other Poems.

- He ‘found himself shaking with excitement in front of one of Monet’s paintings of Rouen Cathedral‘ (p.20). And Chartres knocked him out.

- He bought into the communicative power of photography. In his seminal Oxon guide (1938), part of the Shell Guide series famously published over many years with John Betjeman, Piper launched a veritable imagetext. Under John B’s guidance of a ‘surprise on every page’, it reads more like a diary than a Pevsner-esque listing (pp.107-109), with the majority of images being Piper’s own. As well as the vernacular documentary style, Piper used a photographic negative of a collage for the endpaper design of the book. He thought the aerial photographs of the journal Antiquity (O G S Crawford) were ‘among the most beautiful photographs ever taken’ (p.123), as they revealed the layered nature of the landscape and of looking. Like Monet, he had a darkroom built near his studio (late ’40s), and in the ’60s, he was one of the first to regard photo-lithography and photographic screenprinting as a means of artistic expression – eg. Eye and Camera series (1970s) and A Retrospect of Churches book (1964).

- He loved Ruskin. Modern Painters was a favourite book, as was the Ruskin quote, “There is nothing I tell you with more earnest desire that you should believe than this – that you will never love art well till you love what she mirrors better” (p.129).

- He was pioneering in his contribution to and encouragement of churches engaging with contemporary art. Which didn’t necessarily mean the subjugation of art for solely illustrative purposes – originally it was the ‘transforming effect’ of stained glass on the architecture and its ‘creation of an enclosed, escapist world of colour and modified light’ which inspired him, more than the visual teaching of the Bible (p.361). He curated The Artist and the Church in 1943 in Chichester Cathedral, including modern mural designs as well as his favourite 10th century stone carvings. He exhibited in the Prophecy and Vision exhibition, which toured in 1982 to Arnolfini in Bristol, among other places. In between, he consistently straddled the overlapping worlds of art and church, with endless commissions in stained glass, tapestry, mosaic, Christmas cards, bookcovers, vestments, paintings, as well as sitting on committees like the Friends of Dorchester Abbey, and the Oxford Diocesan Advisory Committee.

- He had a studio at home, and an amazing wife in Myfanwy, who somehow raised 4 children in a house without basic amenities for years, while writing critically for journals and newspapers, and with Benjamin Britten on librettos. Their shared love of art, and intelligent engagement with the journey of modern art in Britain (especially on the axis (cf. Axis journal) of abstract painting v. neo-Romantic painting), was foundational to the success of their working lives.

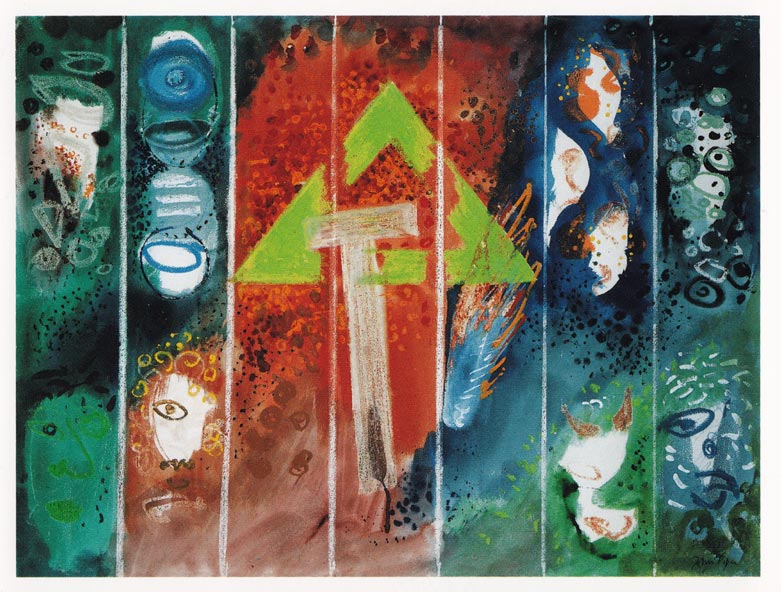

- Piper’s Chichester tapestry design includes the 4 elements. I’ve seen 5 collage, gouache and/or tapestry studies – they affirm my own attempt to linger on the tension between abstraction and symbolism, especially in my Four Elements. Dorchester’s hanging team managed to get the study for earth and air displayed upside-down (note the similar problem in Spalding’s plate 12, compared with figure 21, of Piper’s Forms on Dark Blue). These small mistakes aside, the book and show were immensely inspiring, with such a rich range of work and related encounter. I was overcome.

Header image: Study for Chichester Cathedral Tapestry, 1965, by John Piper