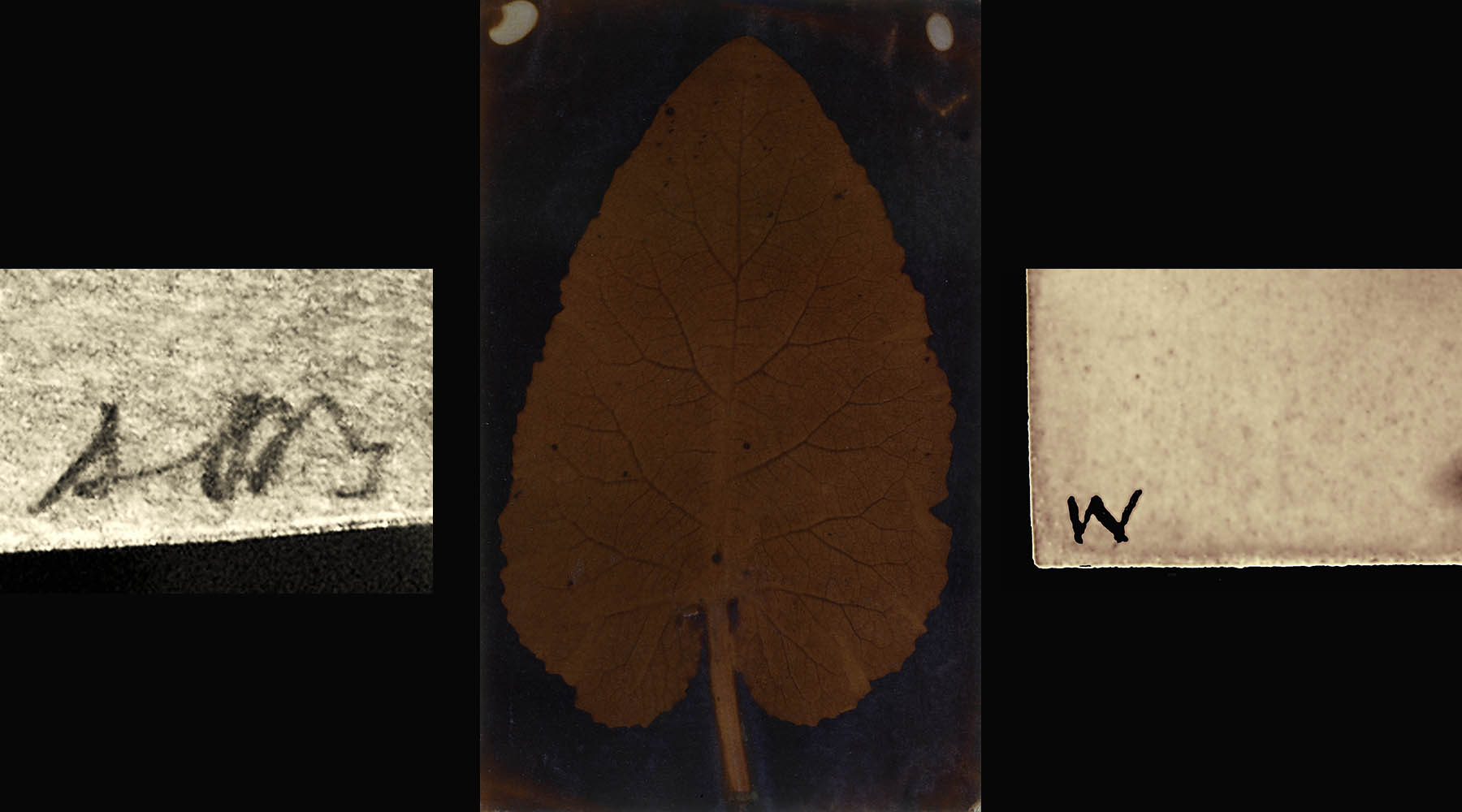

By way of an introduction to the conference Rethinking Early Photography held at Lincoln University earlier this month, Prof Larry Schaaf presented a lecture called ‘The Damned Leaf: Musings on History, Hysteria and Historiography’. In the whirlwind speculation that swirled around this particular photograph, which had come up for auction in 2008 as part of an album, Schaaf’s comments at the time gave rise to unmerited suggestions that it was possibly an earlier photograph than Talbot. The name Wedgwood popped up, since a ‘W’ is found in the bottom left of the negative. In a welcome spirit of openness since the leaf’s quiet retreat from the public spotlight, Schaaf’s lecture gave the photograph its long-due much-deserved critical attention; and the results, while not the tabloid headline so hastily dreamed of, nevertheless open the door on other aspects of early photography.

Of no little interest to me is this early history in Bristol, and the likely female involvement. For Schaaf has discerned in the scrawled lettering on the back of the negative the initials ‘SAB’, standing for Sarah Anne Bright, the daughter of the Bristol MP Henry Bright (1784 – 1869) whose residence was in Ham Green. That the image is printed on paper produced by William West (of the Clifton camera obscura and the Bristol School of Artists) is highly probable – the ‘W’ is a likely link to the blindstamp identifying the paper with the stationer Lancaster, who was selling to West in Bristol at the time. I have written about West in the past (in my book Bristol Through the Lens), as his camera obscura was key to the tradition of landscape composition and view that developed in the South West – a particularly Romantic and photographic view, especially in the area around the River Avon and its Gorge, which includes Ham Green. That the leaf has been treated as a photogram, in the manner of a specimen, is not as far from this Romantic view as we might think.

In my paper for the conference ‘Let There Be Light: Theology and Spirituality in Early Photography’, I consider the vocabulary, context and direct evocation of biblical themes in and around early photographs. Leaves had something of an emblematic status, whether for biological perfection and detail (Talbot), for monogram experimentation (Herschel), or for revelatory apparitions (Enslen); at times, they come close to bearing the immanence of God through the way people saw them, with the action of divine light on the photo-sensitive surface. I argue that when we examine so many leaves, our view should not thereby forget that there was once a forest – that background milieu of religious or spiritual understanding. Nor need we suppose that we have ‘clear’ sight now, rather that we are grafting new philosophical perspectives into early photography.

Two things pointed this up to me mostly clearly at the conference: the first was the final question put to a panel at the end of the last day, a question that sought an answer to our persistent search for photographic origins, for photographic ‘firsts’. Amidst the general replies that questioned points on a historical line rather than the existence of the line itself, I found myself offering the comparison of linear photographic perspective: within its system, we can continue to plot and map our direction and position – but beyond this, surely we have all already woken up to its system-like nature, to the limitations of it, indeed to the falseness of it? And isn’t it in fact photography itself that has done this – in our increasing awareness of its subversion of normative perspective? So the question of origins needs a rather more radical a-historical discussion.

Secondly, 36 of the 52 speakers at the conference were women. In a varied programme that crossed several disciplines internationally, from geography to history, from literature studies to conservation, this high representation of women to me suggests the lack of entrenched patriarchy in what is still a relatively young subject. It bears the mark of the social eclecticism which was undoubtedly a contributing factor to Sarah Bright’s involvement in photography, though here it’s rather more an academic eclecticism. Practicing or studying photography, it is remarkable that so many women are telling the story, which volunteers another radically new, still unrecognised perspective.

Header image: Prof Larry J Schaaf’s revelation of 1839 leaf photograph as by Bristolian Sarah Anne Bright, 2015 presentation.