NOTEBOOK SPOTLIGHT: Genesis and The New Passage

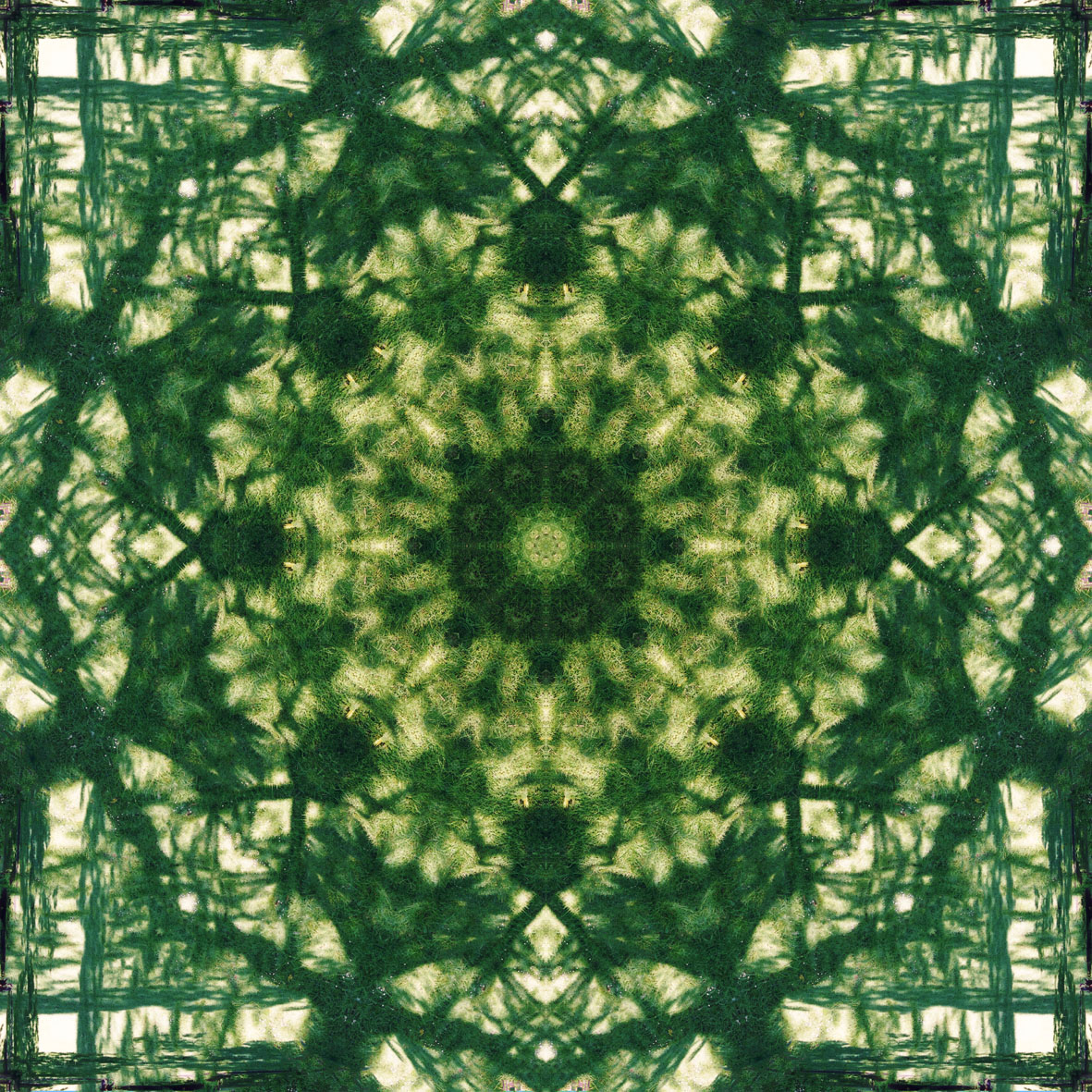

Genesis was created from 60 photographs, taken from incrementally different angles, of butterfly wings suspended in a fish tank; The New Passage was created from 12 photographs taken at half-hour intervals from this spot on the Severn Estuary, UK. In each case the images are interlaced by a computer programme which creates a file for printing and mounting behind a Perspex lens.

The lens is a ridged sheet, whose ridges (or corrugations) affect the passage of light reflected by its surface in such a way as to recreate a stereoscopic effect: human eyes see in stereo, where the slight difference of perception between each eye registers differentiation of depth and movement in the scene before them. In Genesis, the image appears to have three dimensions when viewed by human eyes; in The New Passage, an effect of animation is recreated as the viewer walks past the image.

These pieces are my first explorations with lenticular production as a digital-and-physical process (see Face-Off for a physical way of building a lenticular), for which I engaged the help of Jake Purches at Lenticular Europe in 2011. It’s an advanced technology, and a high degree of precision is vital, particularly when aligning the interlaced print with the ridges of the lens. Unless complete alignment is made, the effect will be interrupted or ‘ghosted’ by images out of place. With alignment, however, the image seems to assume a kind of inner life. Light itself fills out and animates the viewing space, recreating an almost holographic depth. The higher the frequency of the LPI, or lenses-per-inch, the more seamless and holistic the depth/animation effect.

What to me is so captivating about lenticulars is that they deepen the viewer’s engagement with the print in person – the effect cannot be apprehended through a screen – and so a more charged, immersive relationship with the subject depicted is part of the encounter. The commercial uses to which lenticulars are often put (for example in merchandise for films, or in tourist souvenir prints) tends to capitalise on this sense of something uniquely available to the viewing eye which is also an object of delight. They can, and have been, mass-produced all over the world. They’ve been taken up by few artist photographers (for example, Jeff Robb, and Chris Levine’s famous lenticular portrait of the Queen) – they are not cheap to make, and developmental/experimental expertise requires extended time and budget. I hope, DV, that this might be a craft I can build on, bringing my own vision of renewed creation to deeper light.

The pieces here were accompanied by the following text panels when first exhibited in 2012. They are linked by biblical accounts of beginnings, of the world unfurling at the first moments of creation (Genesis 1), and as the Israelites began their liberated journey out of Egypt (Exodus 14).

Like other ancient Near Eastern accounts, primeval water and darkness set the scene. In contrast to these accounts however, which stress the combative struggle to create order, the presence of God’s Spirit acts almost effortlessly to choreograph the generation of life. ‘Spirit’ translates as both ‘breath’ and ‘wind’, combining the sense of both a human closeness and a powerful meteorological force. Like the well-known butterfly effect, the smallest and most delicate movement in air can cause massive planetary change. Butterfly wings in this image also refer to the ancient symbol of the soul, which in art became a Christian symbol of the resurrection and rebirth.

Genesis (2012)

In the 18th century, at a point on the Severn Estuary called ‘The New Passage’, John and Charles Wesley crossed over to Wales from Bristol in order to spread the Christian message. The ferry crossing would have needed to negotiate a 2-mile span of water with the second highest tidal difference in the world: in this image, photographs taken at half-hour intervals capture the water’s progression at the perigean spring tide.With such a pronounced difference, the Severn’s tide emphasises the dangers of journeys which involve river or sea crossings. What is a matter of overcoming a geographical boundary often becomes symbolic of a metaphysical transition, a journey to a new form of life. This recalls the biblical account of the exodus of the Israelites, for whom the Red Sea parted to allow them to escape the Egyptians. It also suggests water’s role in baptismal change: the earth’s patterns evoke a sacramental theology, symbolising renewal and cleansing.

The New Passage (2012)

Header image: First and last image in print sequence of Genesis, 2012, by Sheona Beaumont.