On a Thursday in Lent, I found myself at Chelsea College of Art, in their Banqueting Hall, for an evening performance/service by Mark Dean, Pastiche Mass. Supported in his position as Chaplain at the College, Mark presided over a service that included the invitation to receive communion, as well as the traditionally sung elements such as the ‘Kyrie’ and ‘Sanctus’. In each case instead of communal singing at these points, Mark played 5 videos with sound whose references to tradition were reflected in some way through the choice of appropriated and manipulated footage – of music performances and their dissected visualisations. Aretha Franklin, Nina Simone, The Human League, The Revolutionaries, and the singer Ade Bamgboye (seen above) were all part of the liturgical mash-up. As such, Dean was leading a service with a nod to the mixed-repertoire concert performance of the mass, as much as to its congregational setting in worship.

It’s a moot point as to what kind of balancing act was achieved with this pastiche. In print, the form of the order of service gave structure and rhythm to the event: in front of me I had a sheet of paper taking me through what was happening, coordinating call and response within the familiar enough format of the Church of England’s Common Worship for this service (even down to the colour coding and typeface), interjected with images of stills at the relevant moments. I rather like the illumination here, the idea of a breakaway flash of revelation that is yet included in the programme. Dean has referred to the ‘pre-existing form as a discipline’, within which other ties to religious expectation fall away, such that author-controlled or viewer-controlled inferences are disbanded through something received as a given. The best liturgy has that liberating effect, the knowing of its pattern by rote and the repeating of its cyclic themes through the church calendar becomes a trigger for a bigger expanding experience, connected to the consecration of our human experience of time. I’ve no doubt that Dean’s ideas for his work grew from this feeling for liturgical performance, partly because it is itself pastiche – creative reshaping and returning to sources that is far more than interpretative commentary. Partly too of course because he is a priest by training.

In fact the wealth of the Christian tradition within which Dean practices derives from re-interpretation understood via imagination as much as via intellect. The Bible’s New Testament reimagines the Old in various ways, in Jesus as prophet, a new Adam, a light to the Gentiles, etc. Metaphor and imagery ricochet off the pages, and its pastiche language becomes something used to bring ‘affective sense’ to the fore – a deepening of human knowing through a kind of intuitive connecting (cf. Richard Dyer, Pastiche, 2007; and Michelle Fletcher, Reading Revelation as Pastiche, 2017). Readings during the service could have been part of this homage to image-text spiritual connection, but were instead, as read by invited others, an interruption of slightly awkward relational ‘live action’ to the otherwise more scripted performance. In fact, the delicate suggestiveness of word play, image, and sonic concept as a whole was undermined by moments of jarring reality happening outside the linguistic frame (or ‘discipline’): adjustments of the microphone, Dean standing in the projector’s light, apologetic accompaniment to the starting and stopping of the films, the moving across/between readers. I also felt the incongruity of the Banqueting Hall rather strongly, to something I had come to as a service first, performance second. To others I spoke to who had come with performance in mind first, it was the service element that was incongruous, a perpetuation of odd ritual to be viewed askance in the name of art.

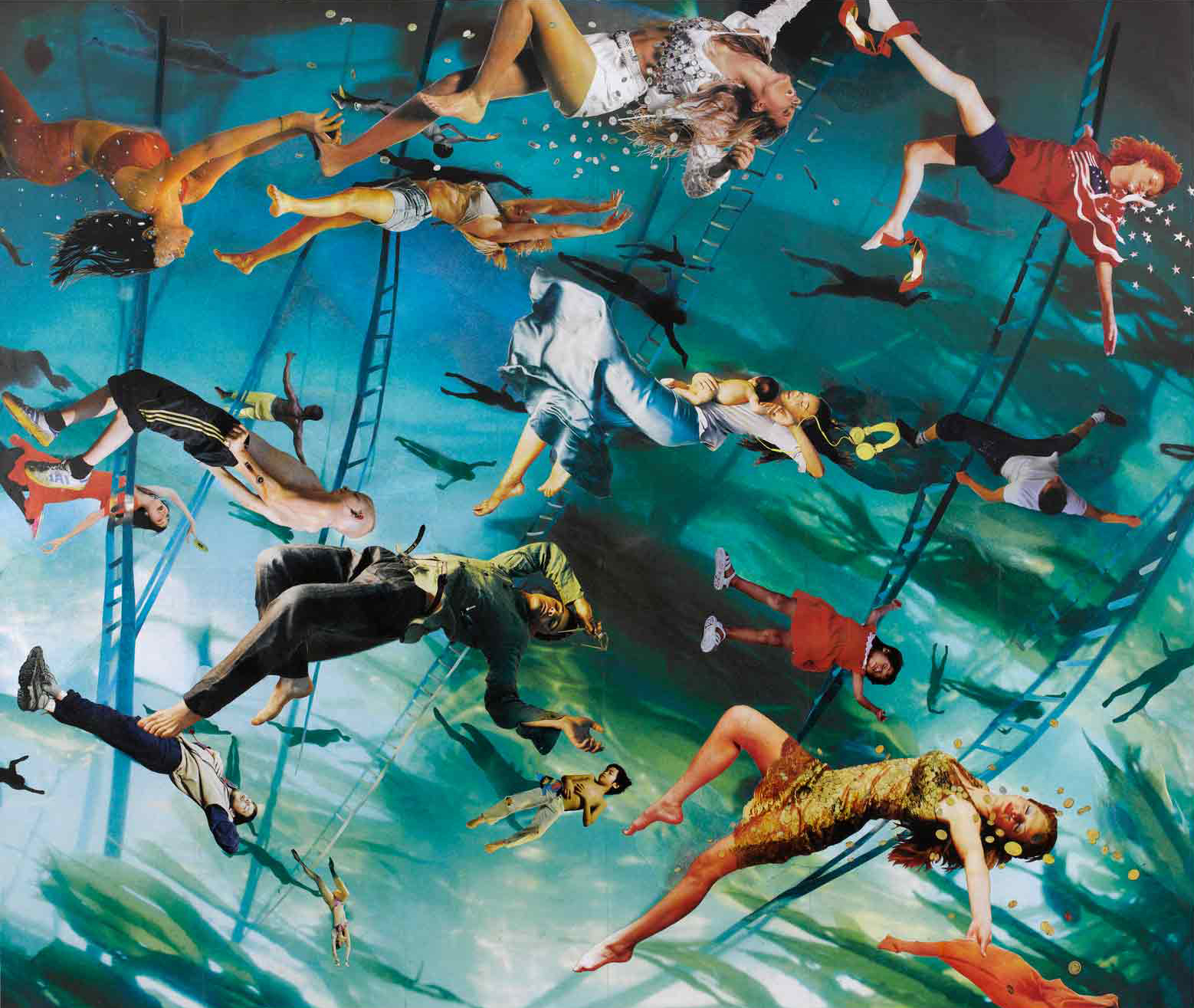

Unusually perhaps, this inside/outside discomfit was telling of genuine middle ground. An out-of-place awkwardness in a church building, while felt by many today who find themselves there for a baptism or wedding, is usually set against the ‘known’ ground of the congregational faithful. Similarly, the out-of-place awkwardness of religion in a gallery is increasingly set against the ‘known’ ground of art world intellectual engagement. A no-man’s land lies between – except perhaps for what Dean has stumbled upon in his church-supported context for art and art-supported context for church (Dean was engaged by the Arts Chaplaincy Project and Art+Christianity). Where I think he succeeds in exploring this space is in the film Credo, the only one incorporating Dean’s own direction in its making. Here, Bamgboye sings the apostolic creed, singly at first, then at interval with himself a second and third time. The setting is, to all appearances, a church, and the performance is in the physical place of congregation: a doubling and tripling of sound from a reality in which we are implicit. This surely seems the closest to liturgical resonance, to something demanding affective response, in Dean’s piece as a whole.

Header image: Credo, 2008/16, film by Mark Dean. Image used with permission.