Earlier this year, my first journal article from my doctoral thesis on the Bible in photography was published in History of Photography. The journal itself has been a prompt many a time for my research – its articles shine so many lights into the past, with deeply attentive and close looking into histories that haven’t yet been told. It is the authoritative journal for close, peer-reviewed, study in the subject. So I’m naturally delighted that this article was accepted for publication.

‘Photographic and Prophetic Truth: Daguerreotypes, the Holy Land, and the Bible According to Reverend Alexander Keith’ (Vol 42, Number 4, 2018, also published here on my website) explores Keith’s bestseller publication and his use of engravings made from daguerreotypes to ‘prove’ that biblical prophecies about the landscape of Palestine had come true. Early ideas about photography’s ‘truth’ are commonly filtered through our modern understandings of science, objectivity, and experiment, which tend to present a blind spot when it comes to religion. Particularly in regard to Christianity and the Bible, religious reference is reduced to thematic illustration and (a nostalgic) art iconography. My essay presents an important challenge to reductionist simplifications of Christian thinking prevalent in early photography, revealing the intellectual sophistication of what is Keith’s photo-biblical apologetic. His highly articulate faith-based defence of photography’s superior documentary capacity reveals a more complex relation between science, visual culture, and religion than has typically been assumed.

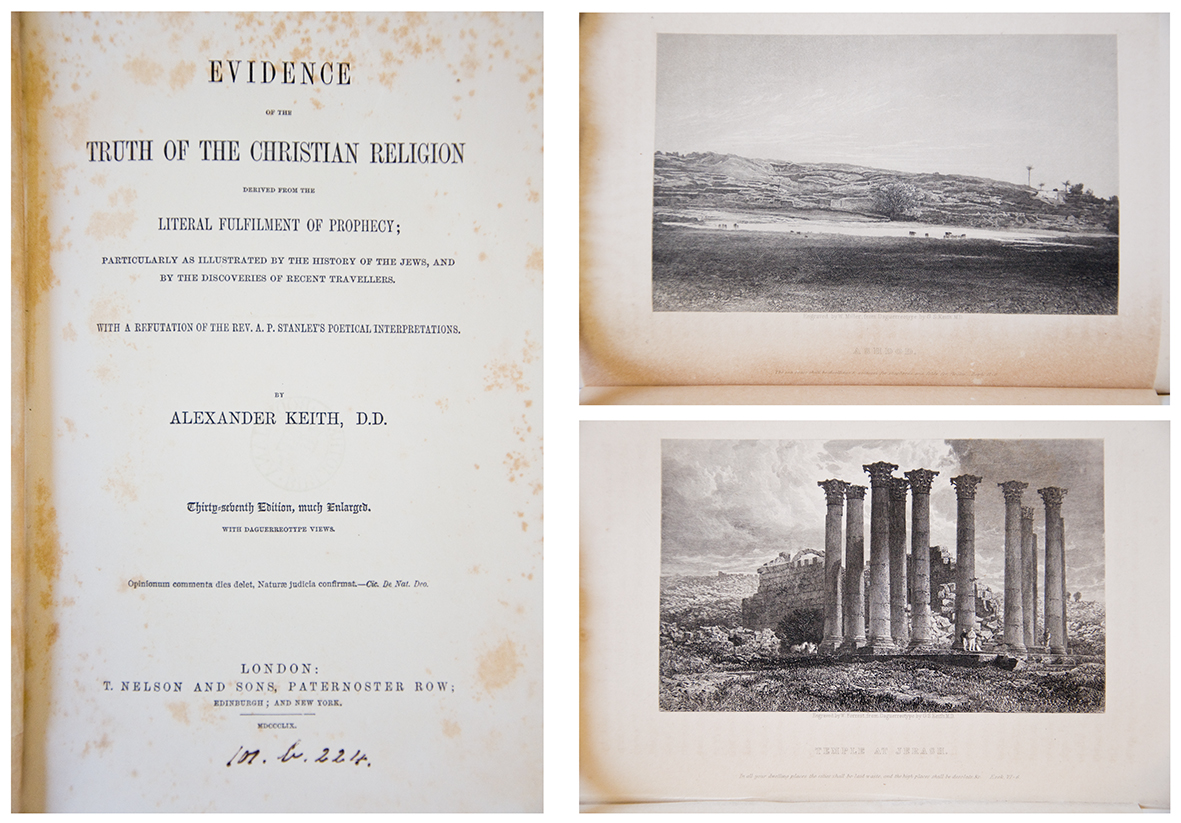

For his book, Evidence of the Truth of the Christian Religion Derived from the Literal Fulfilment of Prophecy, Keith employed the services of his son George Keith to daguerreotype biblical sites on a tour of Palestine in 1844. The 18 engravings from daguerreotypes might look a bit dull, but they had the punch of truth-telling propaganda in their day: seeing was literally believing. This was more than armchair travel, more than seeing equating to the real experience of being there, because Keith linked the images to specific texts from the Prophets. In the above images, Ashdod (west of Jerusalem on the Mediterranean coast) shows that ‘the sea coast shall be dwellings and cottages for shepherds, and folds for flocks. Zeph II-6’, and the Temple at Jerash (east of the Jordon, a city not readily identified from Old Testament references) reveals that ‘in all your dwelling places the cities shall be laid waste, and the high places shall be desolate, &c. Ezek VI-6’. Keith made the record of the photograph synonymous with the record of the prophets. No other Palestine-religious guide (and many would follow in the nineteenth century) would hold photography and the Bible so determinatively together.

Ordinarily, it’s not a complicated connection, though it’s often missed because of common understandings of the Bible-as-myth today. The Bible is a record first-and-foremost. Its declared intent is overwhelmingly documentary, it purports to be historical about the Israelites in the Old Testament, and about Jesus and his disciples in the New Testament. Though it certainly has more lyrical and poetic books or sections, it is not as a whole a mythical account of a religion’s origins, nor a theological treatise. This is its ‘scandal of particularity’, as it has been called by theologian Alan Richardson. Keith, however, takes this one step further, because it is the predictions of the prophets that he takes as literal record, their foresight about the landscape’s destruction. And for his purposes, it is helpfully specific in the text about what the desolation will look like. Writing at time when British interest in Palestine was expanding on the tide of the Empire’s wealth, it was a land increasingly present to readers of the Bible too, and of concern particularly to Zionists. Keith had such concern in mind with other publications, notably Narrative of a Mission of Inquiry to the Jews from the Church of Scotland (1842), which had first employed him in Palestine in 1839. What one was engaging with when one looked at photographs of the Holy Land was urgently related to religious convictions pressing through the literalness, and bound up with present feeling about who was entitled to the land (especially when it was so conveniently photographed as empty). It was nothing short of a symbolic reality: the Jewish Promised Land inviting ‘return’, as much image as word.

For writing about photography, I think it’s urgent work to recover such a religious conviction as Keith’s, or at least to give those who held it (he had thousands of readers at a time when over half the population went to church, his book running into over fifty editions) the benefit of the doubt when it comes to their intellectual capacity. We can attribute greater specificity to their intentionality, if not always circumspect to our eyes, in the name of a fairer, clearer, interpretation. If nothing else the biblical literacy of our ancestors in the West ought to be more fully reckoned with, and given its fine grain. In my article I expand on this through the idea of Keith’s telescoping across present feeling and original prophecy, and through photography’s quasi-supernatural promise as being made ‘without human hand’. If anyone reading this would like a hard copy of the article, let me know and I’d be happy to send you one.

Header image: From the 37th edition of Revd Alexander Keith’s publication in 1859. Photograph by Sheona Beaumont.