At this time of year, first-day-at-school photographs are all over social media. I can’t help but join in, the narrative of my children’s lives weaving into my own. But I’m also consciously reflecting on the way I choose to represent them to myself: the photographs, the albums, the poetry, the birth narratives that began 5 and 7 years ago. That’s all part of a long-term project, Born Again, in which I’m exploring something profoundly formative about the journey of early motherhood – and in particular, the forms of self-representation that I choose to work with (including among other things, taking part in One Born Every Minute).

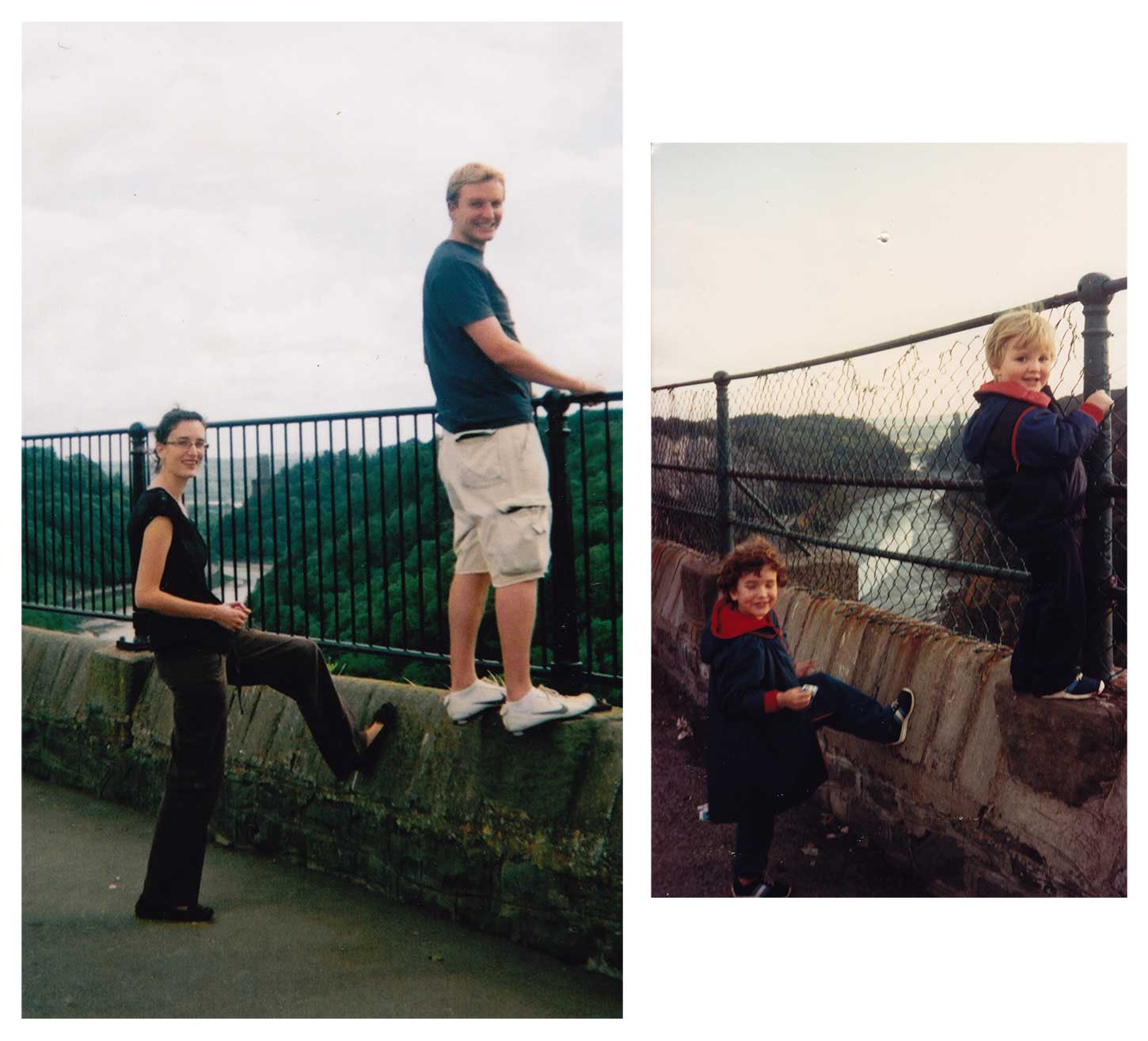

For me, the pairing of my kids, brother and sister, with their own experiences of ‘firsts’ invites the obvious time-travelling comparison between then and now. I see a proportion shift in their limbs, I see older, more intuitively formalised body postures. And in their relationship I see my daughter’s hand on her brother’s shoulder in the younger picture, and I see his toe-pointing shoes in the older. But I also see me: in the reflection in the glass, where my husband takes the earlier photo, and my hovering, which then assumes the photo-taking position in the later image. The kids’ differences, and the different horizons of their ‘firsts’, has my sameness in the background. There I am, 3 years apart, doing the same thing, attentive even to the fact of sameness when I took the later photo, wanting to recreate the scene. That effort, paradoxically, was based on sameness, but intended to render change visible – a change that I am part of, and feel part of. I don’t think it worked, because I can’t foreground my feeling about it other than by writing here. Though perhaps indeed, that’s why I’m doing it. Some insightful people writing about photography have put their fingers on this:

The legibility of a presumed relationship in time was the backbone of a system of visual representation underwriting some of society’s most fundamental beliefs about itself. These beliefs are registered not only in the temporal realm but also in the photographic image’s fraught referential relationship to the ‘real’ object or event it depicts. This linkage has always been a cornerstone of photographic theory, oscillating across an evidentiary spectrum, from a positivist view of a transparent connection between the two to a thorough skepticism of the medium’s ability to tell any kind of truth. Before-and-after pairs disrupt each end of this belief spectrum, paradoxically, by embracing both of them. They depend as much upon the evidentiary aspects of visible temporal bookends as they do upon acknowledging that the more powerful way of articulating the central event is to leave it unseen. The before-and-after pair relies on the imaginative participation of the viewer, thereby diverting attention from the ‘proof’ of the photographs toward the viewers’ own – necessarily subjective – interpretation.

Kate Palmer Albers and Jordan Bear, in Before-and-After Photography: Histories and Contexts (Bloomsbury 2017), pp.4-5.

My imagination in these images ends up taking a bit of a detour – since I feel thwarted by the evidentiary primacy of comparison invited between my kids, I mentally superimpose another effort of comparison with which I do have a deeper pictorial association – a posed recreation of another brother-and-sister shot, this time of me with my brother. In one I’m about 8 years old, in the other about 28. Yet now I’m thwarted by too much reality, the bookending is a rather blunt tool. It turns out that I’m consistently trying to turn my attention to writing ‘in between’, to the the invisible spaces that we occupy around and between photographs. If my practice is indeed a book, perhaps the image-making is only ever the cover, the boards, or the book-ends. It’s the exercise of writing and research whose pages fill out the story, that invite imagination in the reading.

Header images (l-r): First days at school, 2018 and 2015. Photographs by Sheona Beaumont.