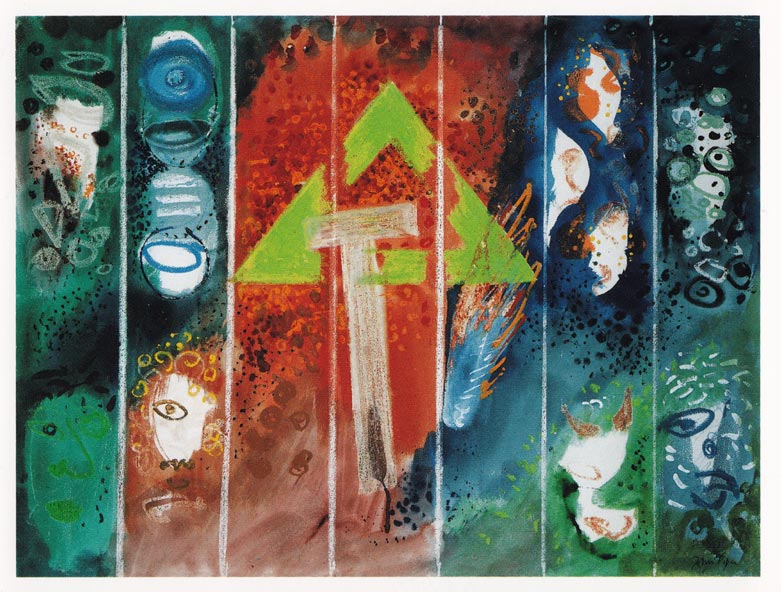

On until 6th May, Bath Abbey is hosting 7 works by contemporary artists under the heading ‘Odyssey: A Long Journey in Which Many Things Happen’. 7 pieces, on paper, doesn’t quite seem to add up to an odyssey, but surprisingly, such is their thoughtful placement in and interconnection with the abbey’s spaces that it feels expansive in the flesh: an opportunity to soak up the resonances of carved or pictured forms in the multi-level languages of ancient and modern.

In fact, such close attention is paid to the siting of the works, that the dialogue between church and art becomes quite a lively one – which is unusual when the context for contemporary work is more often than not a white cube, resistant or even hostile to any community, let alone one with gargoyles and rood screens. So David Mach’s Jacob’s Ladder, 2010, has a conversation with the stained glass window above it showing the ranked descendants of Jesse (as well as the famous sculpted ladders outside at the west entrance), and Damien Hirst’s Saint Bartholomew Exquisite Pain, 2006, is in a chapel dedicated to the martyr St Alphege. If the text alongside the work were overlooked in raising such connections, visitors may well find conversation is literally generated by the vergers or other staff present, whose engagement is a delight.

What seems most rewarding of all, however, is the chance to quietly discover one’s own relation to the works and in this case, for me, the three pieces by Patrick Haines steal the show. Steal the soul might be a more apt phrase. Perennial, 2009 (above), is a 12-foot disconcertingly spindly sculpture of a giant hogweed. With its roots bracing against the bare floor, resisting earth-bound anchorage, it has all the menace of a triffid-like presence (warranted, in fact, by hogweed’s extreme toxicity in real life), until you notice the goldfinch curled and encrusted at its ground-level root ball. It has the red marking, as well as a thorn in its gold beak, a relic of and sacrifice with Christ’s death on the cross. It is so mute, so poignant, that on kneeling at the altar rail to get a closer look, one can’t help being drawn into its story, its passing. Similar smallness is felt in both Grounded, 2013 and Chapel Flight, 2013, where a dragonfly on a service book and a miniature skeletal chapel frame evoke something like an interior fragility. The poise of organic and creaturely life is given poetic and spiritual celebration in all these pieces.

The two remaining works by Koji Shiraya (After the Dream, 2013) and Tessa Farmer (Voyager, 2013) are physically more demonstrative. The former fills the Gethsemane Chapel with dented porcelain spheres, which tumble across steps and altar and the latter has installed a swan in flight in the Birde Chantry whose wing-tips fan out nearly edge-to-edge with the walls. Both have a rapidity and a flow, a sense of life briefly halted, though channelled by the space: Voyager in particular seethes with parasitic ants and other animals. Like Haines’ goldfinch however, the swan and the delicate butterfly wings impressed on its beak, stand out regardless of scale as stubborn symbols of loyalty and love – all the more so in their sacred settings.

Header image: Perennial, 2009, by Patrick Haines. Photographed by Sheona Beaumont.