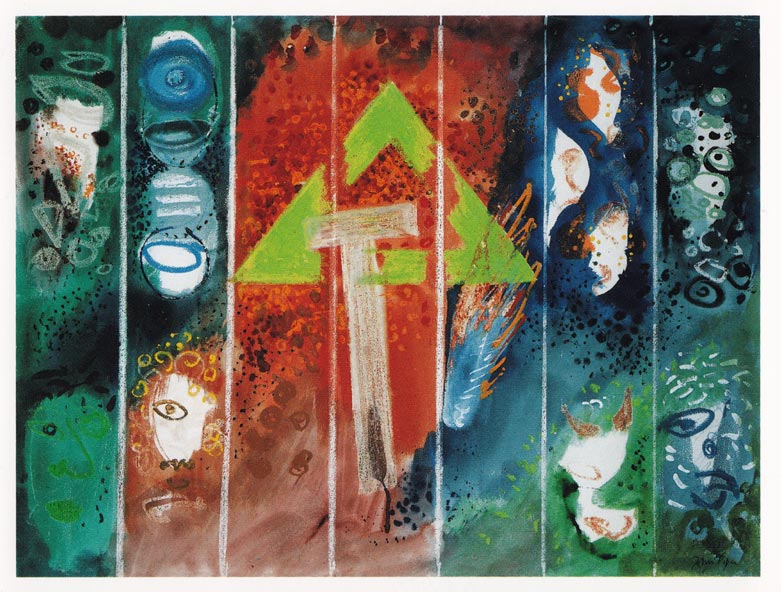

A year on from husband Adam’s deaconing service at the start of his curacy, I found myself sitting down again to play with textiles, symbols and deadlines. The brief: to produce a design for a white chasuble, to be worn at his first service leading communion and with the stole I produced last year – see the blog post.

The visual impact of this vestment is completely different to a stole – so the language of pattern and motif is more about emphatic statement than personal code. The wearing of it involves having your back to the congregation at times, as well having your arms crossing in front of you. So there is a common range of panel areas which are usually decorated: a chest-height symbol, and/or a central orphrey (stripe) stretching the length of the cloth, sometimes with a Y-shaped branch at the top to go over the shoulders. There are the usual designs – crosses, letters, a chalice. I’m more interested in the less typical ideas, ones which are more representative of the person and the multi-cultural world.

So the theme here is Ghana – the place where it all started for Adam’s journey to ordination, and a Ghana alive with Christian symbols that draw on tribal patterns and custom. On the front, the central dark purple symbol is an Adinkra symbol of worship called ‘Nyame Dua’, meaning altar of God (more on Adinkra symbols here). Literally translated, it means ‘God’s tree’, which in Christian symbolism can be another way of talking about the cross and Jesus’ death. More than just a remembrance of what Jesus went through, communion is about a living encounter, through place and purpose. The where and when of Adam leading communion is an important part of what worship is, and how the worship is (including his own) – where symbol becomes sacrament, that outward and visible sign of an inward and invisible grace. Beyond this main focus, the red fleurettes are extensions of the tree metaphor (life through blood), and the gold details embellish and link the lines of pattern. Colour and texture come from the tie-dye Ghanaian fabric itself, large parts of which were already embroidered – this is the main feature on the back panel.

With the added dimension of being a personal challenge, this chasuble is again my sticking up for new and fresh takes on traditional craft in church design. This post has a ‘practice’ category because I take it seriously alongside my other, culturally more palatable work. Vestment design is, to quote a friend, ‘theatrical costume with beyondness and meaning’, it does more than you think it does. And, to add to the overall value-raising intention, I quote Nora Jones’ Church Needlework Guide to Vestments (1961), ‘it ought to be pointed out that while we usually expect to pay the electrician for his work in church, we sometimes forget that artists have to live too.’

Header image: Ghanaian chasuble design, 2013, by Sheona Beaumont.