By way of markers to locate some of my emerging research around the image and text relations of particular biblical photographs, here I note the terms from Barthes which I cannot avoid. Benjamin, Barthes and Baudrillard – the three B’s who hang around photography’s dark room like prophets in the wilderness. They script stories of the image which seem like revelation, meditation, oracle – they don’t write like ‘normal’ academics on the subject, they don’t do technological teleology, they don’t inventory a catalogue of styles or meaning. They write the metaphysics of the photograph:

- Early Barthes was more systematic about understanding photographs: The Photographic Message (1961) and Rhetoric of the Image (1964) are like so much structuralist French thought. Here is the ‘denoted’ and ‘connoted’ image, the separated ‘message without a code’ (what the image is of) and its ‘code of connotation’ (what the image means). The ‘photographic paradox’ consists in the apparent dependence-for-success of the latter on the former, especially bizarre when considering that the very objectivity of photographic seeing is a by-word for impartial understanding, a by-word for the opposite of connotative culture.

- To this duality is added (in Rhetoric of the Image) a third non-iconic message, the ‘linguistic message’. The text is an ever-present anchor and/or relay to fix the meaning of the image. Identification and interpretation tie down the denoted and connoted messages (respectively), which are like a dysfunctional surplus of meaning.

- The early photographs discussed by Barthes are press or advertising photographs, which perhaps lend themselves more readily to a linguistic dissection on account of their obvious visual context surrounded by specific practices of showing and reading. What is performed in Barthes’ own writing, he acknowledges as an impossible division of the image, which retains its own ‘flat anthropological fact’ – its ‘real unreality’. Describing the process of representation may rent the image with words, codes, categories, but it does not, cannot, displace ‘the story of the denoted scene … a lustral bath of innocence’.

- Later Barthes found more to write along post-structuralist lines. Camera Lucida, 1980, is more a reflective, searching, and discursive exploration of the photograph’s spellbinding power (noticeably through photographs of people). Though the hints of structuralism remain in a duality now defined by the ‘studium’ and the ‘punctum’ of the image, these are firmly located in the photograph-viewer relation; more specifically, in his own relation to particular photographs. That which is his polite interest, his liking of certain images is the studium; that which ruptures this gaze with a ‘wound’, a jarring detail, is the punctum.

- Such is small-p photography for Barthes – not necessarily different from other forms of 2-dimensional representation. Capital-P Photography (the second half of Camera Lucida), is a diving again for its ontology, a wrestling of its unique identity, via the seminal example of a photograph of his mother (not the image above). The truth of the ‘that-has-been’ has a scandalous effect, ‘something to do with resurrection’, of the tangible ‘proof-according-to-St-Thomas’, ‘the simple mystery of concomitance’. All by way of his own realisation of death and life. Though we may have lost institutional rites for the place of death in society, perhaps the photograph replaces these asymbolically.

- ‘The power of authentication exceeds the power of representation’. The photograph ‘is a magic, not an art’. Art and culture may try to tame the photograph into banality, such that we become indifferent to our relations with reality. Barthes says keep the faith, keep the madness alive, keep the ecstasy: that face-to-face, nose-to-nose encounter with ‘the wakening of intractable reality’.

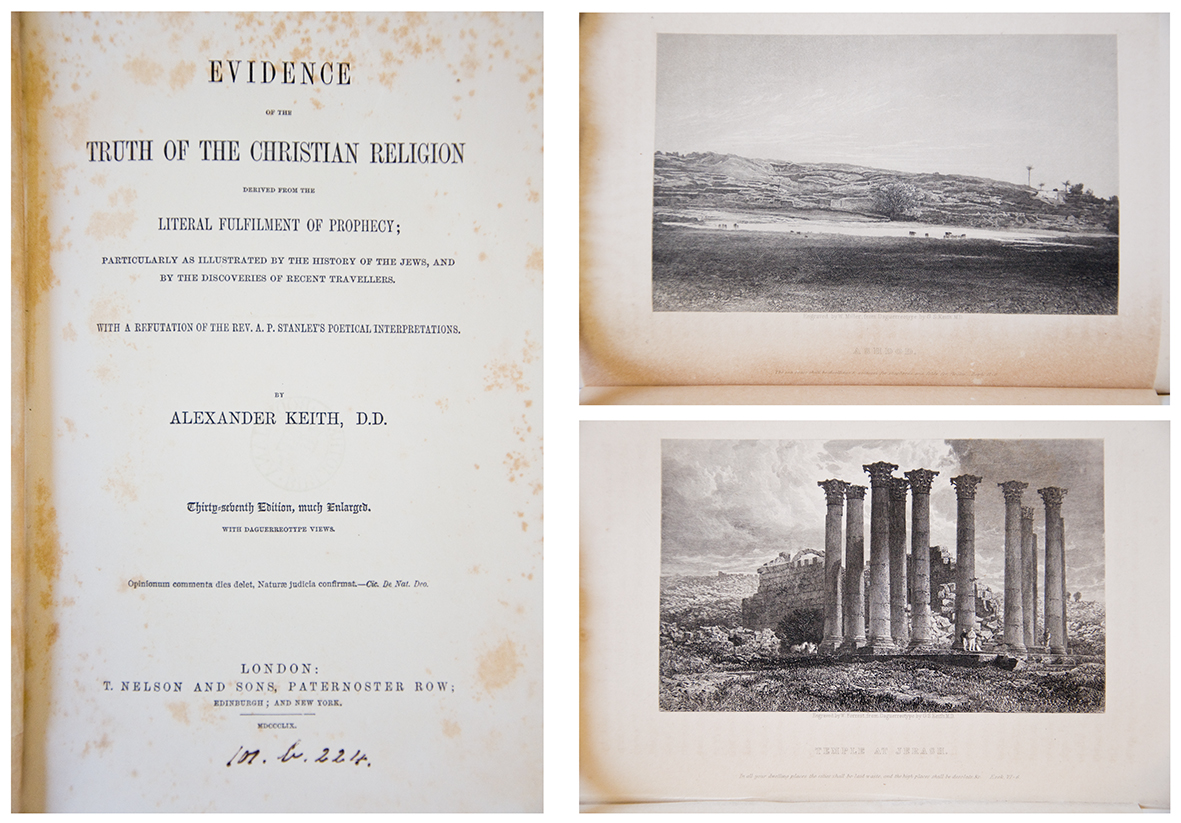

Header image: Barthes and his mother Henriette.