Confused, obtuse, tangled, vacuous, fruitless and one of the most frustrating shows I have ever been to. Jutta Koether exhibits recent work in a display hosted by Arnolfini, Bristol (until 7th July), having toured from Dundee Contemporary Arts earlier in the year. Called Seasons and Sacraments, the work draws inspiration from paintings of the same names produced, serially, by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665). The punchy title is the only thing that carries its weight in the entire exhibition.

Typical of discussions around postmodern painting, this is a display of work that refuses to land anywhere concrete. Display is an integral part of this commentary, as the labels accumulate in corners of the rooms with half-hearted directions to match title with physical piece. Hanging canvasses in such a way as to reveal their reverse is, indeed, to promote painting-as-object rather than as window, and a floor sculpture called Extreme Unction serves to interrupt a doorway into the gallery space. Context – yes, that attention to placement is indicative of painting’s unavoidable self-consciousness ever since Clement Greenberg corralled its reflexivity into/onto itself with Pollock et al.

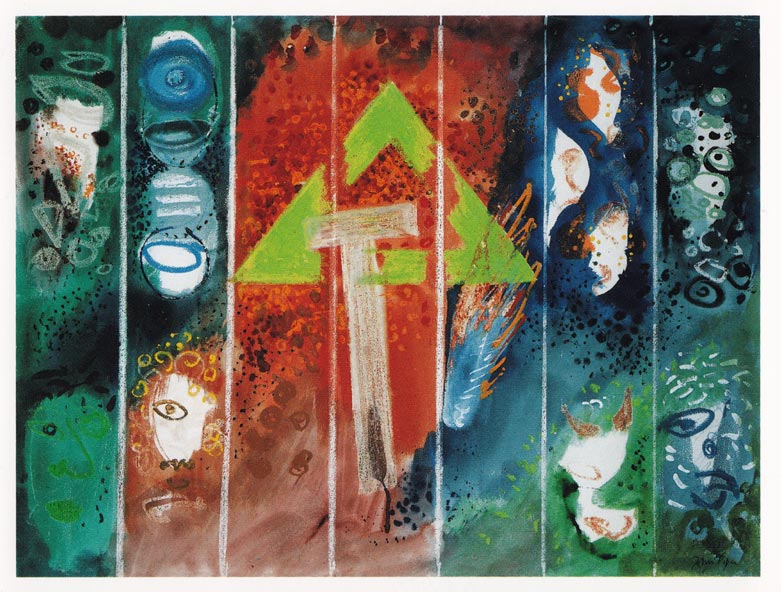

Koether, according to the critic David Joselit (writing in October, 2009), takes this to another level because instead of bringing to light a visualisation of the networks to which painting belongs, she ‘actualizes the behaviour of objects within networks‘. In an interview this year (and through her performance pieces) she confirms this, as she explains that her work contains inbuilt frustration, where comparative readings win out, perpetually thwarting the viewer who would look to settle the issues at stake. So the feel of the paintings seen in the image above, which show 3 of her 4 Seasons, is one of intensity, but also incompleteness. They yield to a behavioural pattern, which Koether calls ‘propositions about painting, not just surface.’

The trouble is, this exhibition also has an inbuilt referentiality – to Poussin, to his kind of painting, to his titles. We may not know the references, we certainly don’t see the original pictures (only fleetingly in Eucharist, a screening of looped photographs of his pieces), but even if the ostensible priority is painting about painting, referentiality gains the upper hand. I find myself angered by a response to Poussin that is demonstrative of a complete ignorance of their content. Or that somehow such content is irrelevant when ‘quoting’ the work in a new context. Painting ceased to wallow in its preoccupation with form a long time ago, we are visually savvy about the potency of content (since Bacon, surely?) – and that is not to say that the old game of traditional, often biblical, meaning and symbolism such as Poussin brilliantly plays is back, but that we form its new context, and so replay it, regurgitate it, subvert it.

In the absence of such involvement in the work, I sought it in the accompanying leaflet provided by Arnolfini for the show. Disappointingly, this too, clearly struggled with Poussin’s place – on Eucharist (showing on the screen above):

The representation of images ‘as they are’ can be seen in the tradition of receiving the Eucharist ‘as’ the body of Christ (and not a symbol), a blurring between representation and presence.

As much as I would love to jump into photography’s discourse about the really real and its appearance, I am insulted by the trite comparison to sacrament. It is not that the meaning of the exhibition-wide references to church symbols and doctrine cannot be enlivened and enriched by contemporary appropriation, it is rather that they are taken here as insincere ‘profound’ labels for a meaning that is decidedly unexplored and unengaged with. Hence:

‘Baptism’, represented by an image of the German racing car driver Sebastian Vettel is a contemporary depiction of idolatry.

A deeper thread of the legitimacy of content in contemporary painting is the twenty-first century context of awakened religion and faith. In the media, post-9/11, the Western secular world has had to face and reckon with an insistence that representation of religion is to be taken seriously, and while the Christian heritage of this country is often a less forthright part of this dialogue, it cannot be ignored. Painting needs to catch up.

Header image: Koether at the Arnolfini, Bristol, 2013. Photograph by Sheona Beaumont.