I’ve spent a lot of time over the last month analysing the iconographic language of photographs by Julia Margaret Cameron. Her photographs of Mary are undoubtedly tied to the realism of a posed, dressed up model who is trying to look like a biblical Mary. But the question I keep coming back to is how the ‘type’ continually resurfaces?

Photography makes the most of a real scene, real skin, real cloth, real symbols in front of the lens. And critics have said Cameron’s Marys are demonstrative of feminine domestic assertion within the constraints of Victorian society’s norms: her Mary lives in the 1800s. But I think there’s something more obvious than this which gets overlooked. Even with all that dressed up reality, her Mary is still iconographically pointing to the original Mary. Rather than an empowering of modern domestic woman, the pointing action of Cameron’s photography seems to look the other way: her model empowers and reveals the biblical figure of Mary.

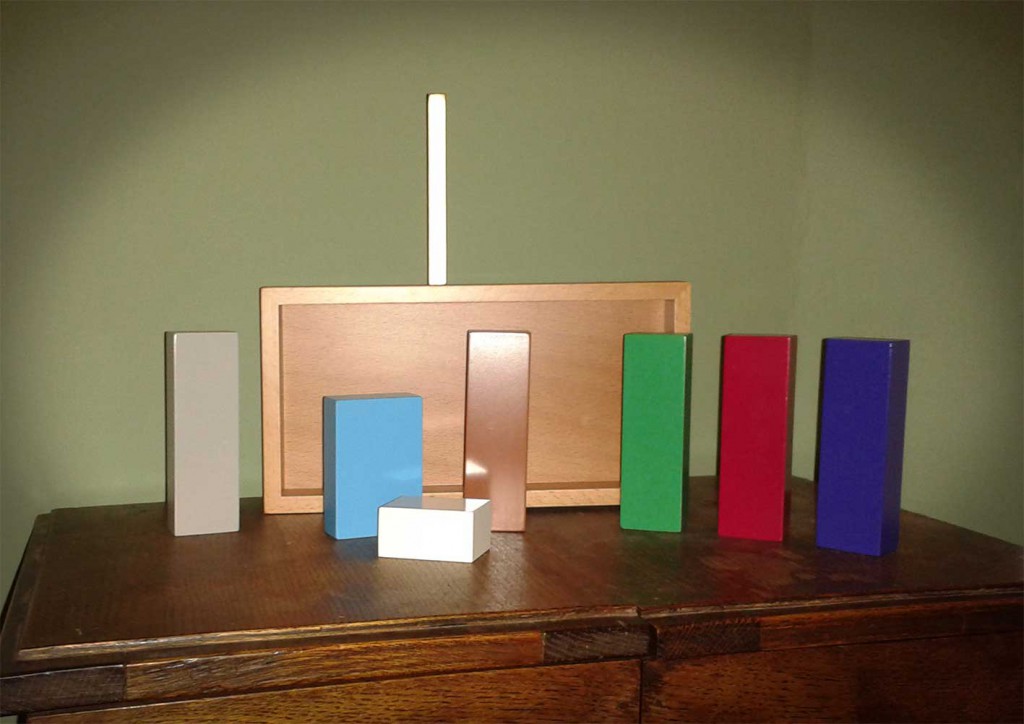

There’s something irreducible about the iconography of Mary. Something that can be captured in the simple blue block of Sebastian Bergne’s Nativity above. Something that works at the level of a sign, which remains visual rather than word-based (see Emilie Voirin’s take on a nativity set). Is it the accrual of years of visual reference (conventional), or is it the way truth lives beyond language (ontological)? Is it a universal stripping down, or is it a fleshed out concept. One thing that photography generally does hang onto is a ‘fleshing out’ – that reality behind, within, around the iconography. Isn’t that an incarnational Christmas characteristic?

Header image: Colour Nativity, 2011, by Sebastian Bergne. Photograph by Sheona Beaumont.