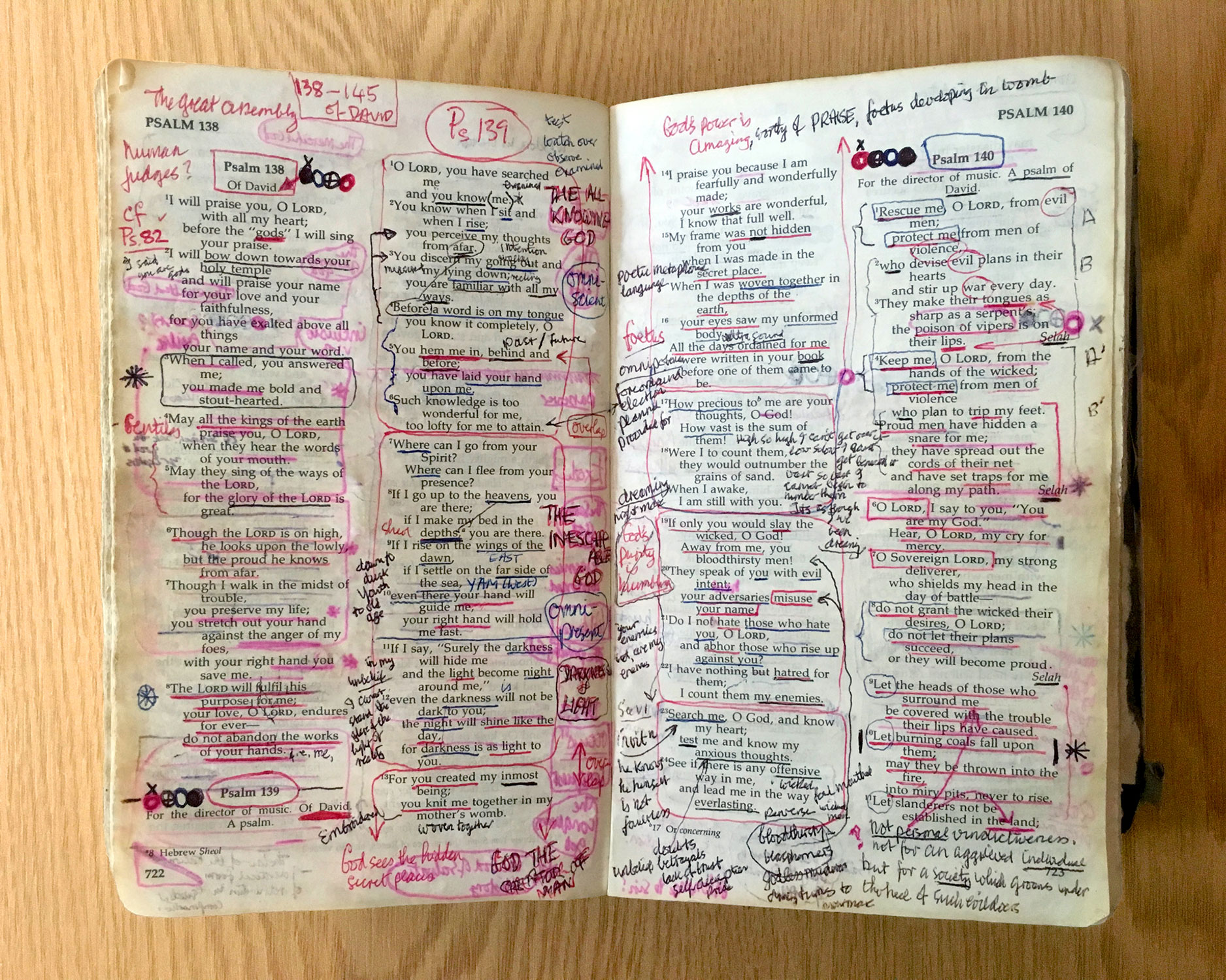

My father died on the 16th April. He had Parkinson’s, and was in a care home in Oxfordshire where, despite isolation, COVID-19 took away his breath. Parkinson’s took away other things, shading my last year with him in other ways: his frustration, his failing speech, his intent on leaving the wheelchair behind (but definitely not the walnut cake). On his last night, the carers read Psalm 23 to him, a man whose love of the Bible knew it inside out. Of all the things I want to remember about my Dad, this is up there along with his favourite jokes and repeated stories of his life’s adventures. He found the Bible to be so abundant, so profusely full of life, it spilled over into my life. And keeps spilling over. The Bible, and this photograph of my Dad’s Bible, is fundamentally generative for me, an evocation of him that escapes the bounds of ‘memory’ and becomes a picture of life to the full.

Which it was. Dad taught in Nigeria, Turkey, Uganda, Malawi, Kenya, and Wales. The first three on that list were all before he was 40 years old, and include what he called his ‘baptism of fire’ introduction to Africa: teaching during the Biafran War at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria, and under Idi Amin’s regime whilst at Makere University in Kampala, Uganda. He was teaching physics in his specialist area of nuclear magnetic resonance (having been first to Oxford, then the University of Nottingham for his PhD), in countries without computers, and usually without running water, but with plenty of guns. Happily for him they also had motorbikes. And mangoes. But the science ultimately wasn’t to hold his interest, and in 1977 he retrained at Trinity College, Bristol, in Greek, Hebrew, and Old Testament studies for theological colleges. His father had been a Classics teacher in Yorkshire, where he grew up, and by his own admission this had put him off subjects in the humanities, but it seemed they were to claim him anyway through a discovery of the Bible, and an adventure in faith. It was at Trinity that he met my Mum, got married at All Souls Langham Place, London, and went out to Malawi ahead of us just after I was born (to Chancellor College, Zomba). By the time my brother was 4 years old, we’d moved to Kenya, where both my parents taught at the Nairobi Evangelical School of Theology, now Africa International University, until 1991.

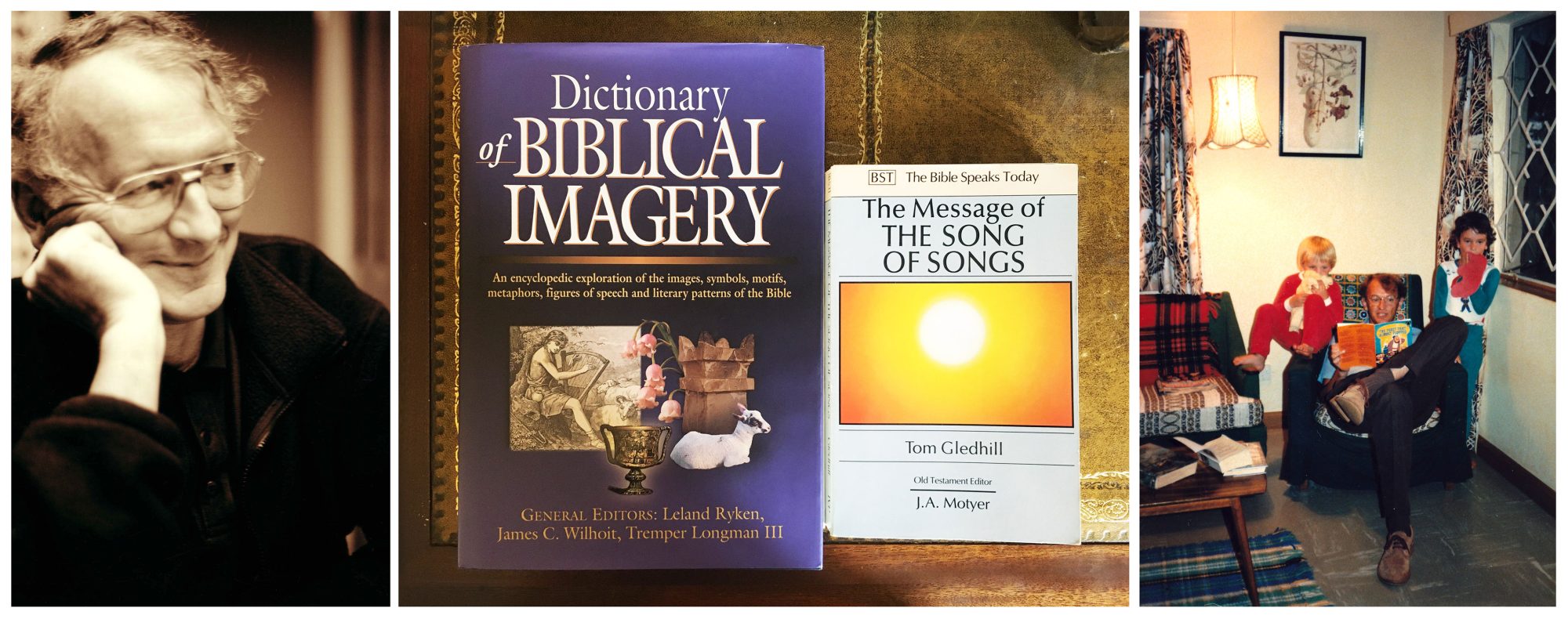

Dad’s faith, from my perspective of a childhood spent abroad, was as vibrant and buoyant as his way with words and stories. He read from or with Bible stories to my brother and I, even into our teenage years (back in the UK). In every home we had a chair that I associate with him reading or praying from, as well as a book-laden study with its own atmosphere of grown-upness. He was a gifted preacher and teacher, and when I compiled a book of acknowledgements for his retirement in 2006, the tributes were overwhelming. He also published a commentary on the Song of Songs (IVP, 1994), and contributed articles to the Dictionary of Biblical Imagery (IVP, 1998) – on ‘Zion’, ‘Trees’, ‘Nakedness’, and ‘Kiss’. His teenage daughter at the time did not think the subjects particularly spectacular, though in a letter I’ve kept he seemed quite proud to tell me that this was an ‘artsy’ effort at biblical interpretation – as I was studying fine art at university. Dad could poke fun at church leaders or traditions (especially the British ones), while speaking with pin-sharp honesty and authority. In UK life, his later experiences teaching in Wales (now the Union School of Theology, Bridgend) kept him in touch with international students, but a wry mockery of everything from rain to Reformed seriousness would pervade what was undoubtedly the loss he and my Mum felt at leaving Africa.

When I think of my Dad, I think of someone who wrote things like ENJOY LIFE and SHOOT THE PREACHER in capitals, whilst facing experiences and people and continents with an unshakeable sense of Christ by his side. He was never overbearing (except to labradors who stole his shoes), but kind and funny and steadfast and bright. I imagine Job’s words, below, as his words (he did love a bit of Job, and always the Old Testament – about which he said he learnt more through African eyes than through a thousand Western commentaries). And I forgive him for lampooning my MA thesis writing style in his wedding speech. I proudly claim artsy wordiness as an inherited trait. To the party in heaven for someone who lived wisdom with such humour, I raise my glass. And put on my sunglasses.

He knows the way that I take;

when he has tested me, I will come forth as gold.

My feet have closely followed his steps;

I have kept to his way without turning aside.

I have not departed from the commands of his lips;

I have treasured the words of his mouth more than my daily bread.

Job 23:10-12

Header image: Dad’s Bible, 2020, by Sheona Beaumont.